In the dry hills of Montemurlo, Italy, above the medieval town of Prato, IPOStudio’s Residential Aged Care Facility grows comfortably from an historic, agricultural landscape, characterized by the traditional dry stone terraces of the region.

This article is abbreviated from the more detailed article in the EBD Journal. view issue

The Takeaway:

- The use of local materials and building techniques reinforces the sense of a familiar home-like environment for elderly residents.

- Unique place identifiers for individual rooms assists with orientation and a sense of personal ownership--in this case, identity is established by the external façade.

- The combination of day centre and residential facilities ensures a strong connection between residents and the local community.

The Detail:

Appearing to support an elevated yard populated by independent structures, a single, punctuated stone wall presents itself to the valley and the city beyond, its curved profile resonating with the contours of the land. For the architects, the site was intrinsically connected to the history of place, “a survivor of new farming techniques that, elsewhere, have reshaped the soil profile”. Combined with a protected group of ancient trees and existing rural buildings, the unique landscape of Tuscany became the conceptual genesis for the entire project.

The idea of context is crucial, not only to the architectural concept, but also to the purpose for which it exists. Research has shown that personal autonomy and familiarity are critical to the idea of home, particularly for the elderly residents of Aged Care homes.12

For the design of Montemurlo, IPOstudio drew their inspiration from locally available materials and a combination of two spatial references: the Convent and the Farmyard, both being relevant, not only in the context of the Tuscan hills, but also because they contain unique communities that are, by necessity Heterotopian3—no apologies for the use of this fantastic word for a place that is simultaneously open and closed —and therefore highly relevant to the unique circumstances of a residential aged care facility.

The farmyard (“aia”) is characteristic of Tuscan farmhouses, a sort of rural "piazza" that provides access to the functional areas that are open to external guests: the day care centre, places of collective life (offices, kitchens and the place for worship) and the main entrance.

Two familiar elements at Montemurlo stand out above all others: The rooftop farmyard-like spaces that provide access to the facilities below and the massive punctuated stone façade that evokes the dry stone walls of the region. Although contemporary in design expression, both features contribute significantly to a sense of familiarity—a place where a home might be made. The topmost access level affords the opportunity for residents to walk unhindered in the open air, in a secure public place punctuated by a series of functional pavilions, some renovated from the existing farm buildings while others are completely new—readily identifiable through the use of lightweight construction, painted plaster and timber cladding. The overall effect resonates with the streets, lanes, farmyards and village squares of the region.

As an architectural device, the curved stone wall extends its purpose well beyond that of the familiar object; it establishes a safe and sheltered wandering path between inside and outside. For the architects it was critical that “the prevailing character of openness and environmental integration require solutions that allow contact (especially visual) with life that takes place outside the building.” Consequently, the diverse cuts in the stone wall not only form a strong façade but, from inside, no two bedrooms are alike and this unique quality assists with way-finding through sub-conscious place identity and personal ownership.

However, the physical setting alone is not sufficient to create a homelike environment—it can only facilitate that possibility. Health Science researcher, Bronwyn Tanner 4, argues that home environment is conceived as having three primary modes of experience: the physical home, the personal home and the social home. Organizational and social aspects of the environment are necessary components in the development of a small, homelike therapeutic setting. This implies helping residents to create a private home distinct from the professional home, allowing residents' personal habits to guide institutional routines and supporting meaningful activities. In one research project involving over 300 participants in the United States, it was found that aged care facilities with a wide variety of shared settings and a strong policy of self-governance, exhibited fewer territorial conflicts than those with a limited choice of social spaces.5 At Montemurlo, the social home is established for residents through the strategic organisation of different functional areas and the strong programmatic connections to the local community.

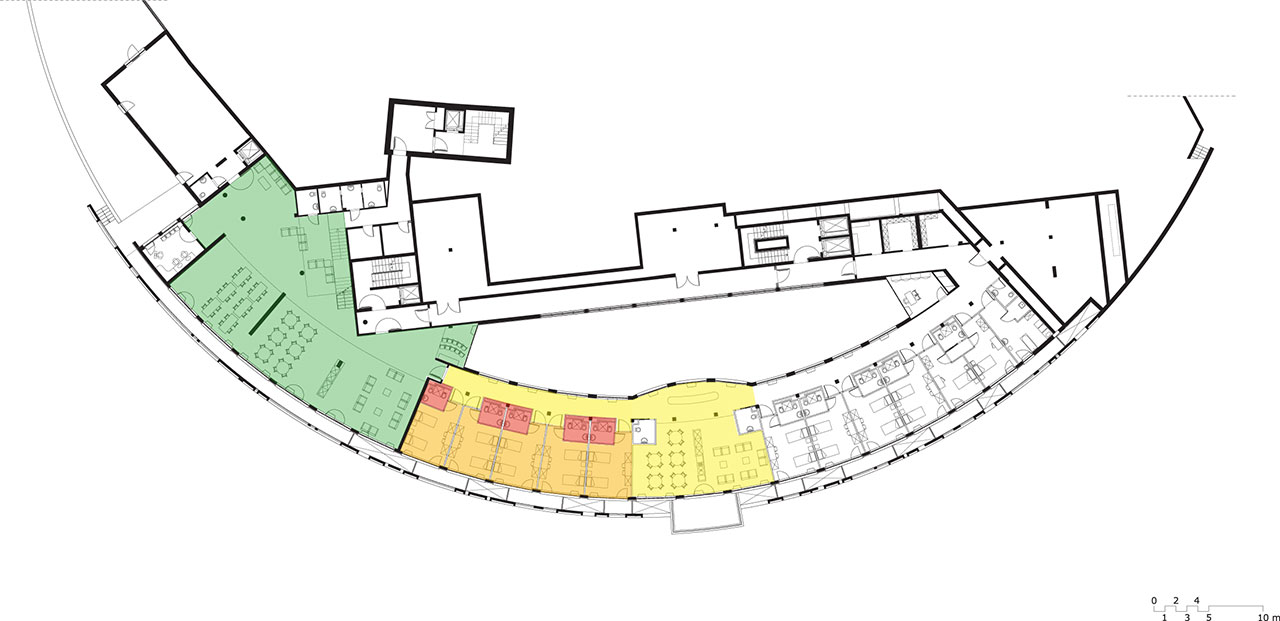

Montemurlo is organised in three distinct but connected social structures, not unlike that of a family home. In the bedrooms, personal territory and degrees of solitude must only be negotiated with one other person. At the centre of each residential cluster is a semi-private social space (yellow)that is used only by those who live on that level.

The smaller scale living and dining facilities, and the availability of more private “niches”, allow residents to choose the degree to which they interact with other members of the ”household”, while ensuring that there is, at least, some degree of connection. Finally, at the western end of level 1, a much larger social space (green) is used for community wide special events and activities, affording the opportunity for residents to interact with the day-centre visitors. The design at Montemurlo provides us with an excellent example of how evidence-based strategies can find architectural expression in a series of layered, socially connected spaces and activities that combine to provide residents with that most precious of needs—the freedom to choose where and with whom they wish to spend their time.6

The Data

Architects: ipostudio architetti

Location: Montemurlo (Prato), Italy

Client: Azienda Sanitaria Locale 4 Prato

Photography: Pietro Savorelli, Jacopo Carli, Ipostudio Archive

Project Completion: 2010

Site surface: 5,305 sqm

Overground surface: 1,155 sqm

Underground surface: 2,505 sqm

Total cost: € 5.073.000,00

-

Nakrem, S. Vinsnes A.G., Harkless G.E., Paulsen B. & Seim A. (2012) Ambiguities: residents' experience of 'nursing home as my home' lntemational Journal of Older People Nursing doi: 1 0.1111 Ij .1748-3743.2012.00320. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1748-3743.2012.00320.x/abstract ↩

-

Verbeek, H., Van Rossum, E., Zwakhalen, S.M.G., Kempen, G.I.J.M. (2009) Small, homelike care environments for older people with dementia: a literature review. International Psychogeriatrics 21:2, 252-264. doi: 10.1017/S104161020800820X http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19102801 ↩

-

Foucault, M. (1986) "Des Espace Autres," and published by the French journal Architecture /Mouvement/ Continuité in October, 1984, was in fact the text of a lecture given by Michel Foucault in March 1967. First published in English (1986) Of other spaces. Diacritics, 16(1), pp. 22–27. The original concept of the Heterotopia was introduced by Michel Foucault in 1967. He conceived of a single place that is capable of juxtaposing several spaces, several sites that are in themselves potentially incompatible. Heterotopias always presuppose a system of opening and closing that both isolates them and makes them penetrable. It is used here to suggest a place that is neither fully closed or open to the world it but must be both, under specific circumstances for a specific group. ↩

-

Tanner, B. Tilse, C. de Jonge, D. (2008) Restoring and Sustaining Home: The Impact of Home Modifications on the Meaning of Home for Older People Journal of Housing for the Elderly. (2008) 22:3, 195-215 http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02763890802232048 ↩

-

Salari, S., Brown, B.B., and Eaton, J. (2006) Conflicts, friendship cliques and territorial displays in senior center environments. Journal of Aging Studies No. 20 pp. 237-252 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2005.09.004 ↩

-

Moyle, W., Venturo, L. Griffiths, S. Grimbeek, P. McAllister, M. Oxlade, D. Murfield, J. (2011) Factors influencing quality of life for people with dementia: A qualitative perspective. Aging & Mental Health, Vol.15, No. 8, 970-977 ↩