Do the physical properties of an exhibition space and/or the way in which art is hung, affect the viewing behaviour of visitors? To answer this and other significant questions, Dr Martin Tröndle and his team of researchers conducted a series of experiments in the St. Gallen Fine Art Museum in Switzerland, between June and August 2009.

Working with the Museum curators, using differing artwork hangings/installations, the researchers sought to test the effects of location on visitor experience and engagement. The exhibition roughly outlined a tour through art history, ranging from Impressionism to the present day, including works from Claude Monet, Edward Munch, Giovanni Giacometti, Max Ernst, Le Corbusier, Hans Arp, and many more. During a three-month period, approximately 70 selected artworks were exchanged or rehung in different positions. During the course of the eMotion experiment, altogether, 3555 single assessments of artworks were collected.

Many research projects confirm our expectations, but provide useful data on the extent to which something is true, or not. Although that is also true of the eMotion project, it also produced some findings that were entirely unexpected. For example:

- Levels of visitor engagement were significantly influenced by the defined function of a space. For the most part, visitors responded strongly to artwork that was located within the boundaries of a clearly defined exhibition space and paid little attention those located outside the official exhibition space The extent to which this occurred was unexpected.

- Objects in a clearly related series attracted more attention than groups of unrelated objects. Three unrelated works by the one artist appeared to attract less attention than a series of three related works and this was contrary to the curator's expectations.

- A poor position can reduce the impact of an attractive object, but a good position did not increase the impact of an unattractive object. In a corner, the normally popular artwork received significantly less attention, while the normally less popular work received the same amount of attention, even though it was in a more central location.

- When individual, but similar, objects are arranged in a long sequence, visitor interest began to quickly dwindle. Although in experiment 2, above, the series of works attracted more attention, when expanded to a sequence of 6 works, the level of attention dropped off significantly after the second artwork.

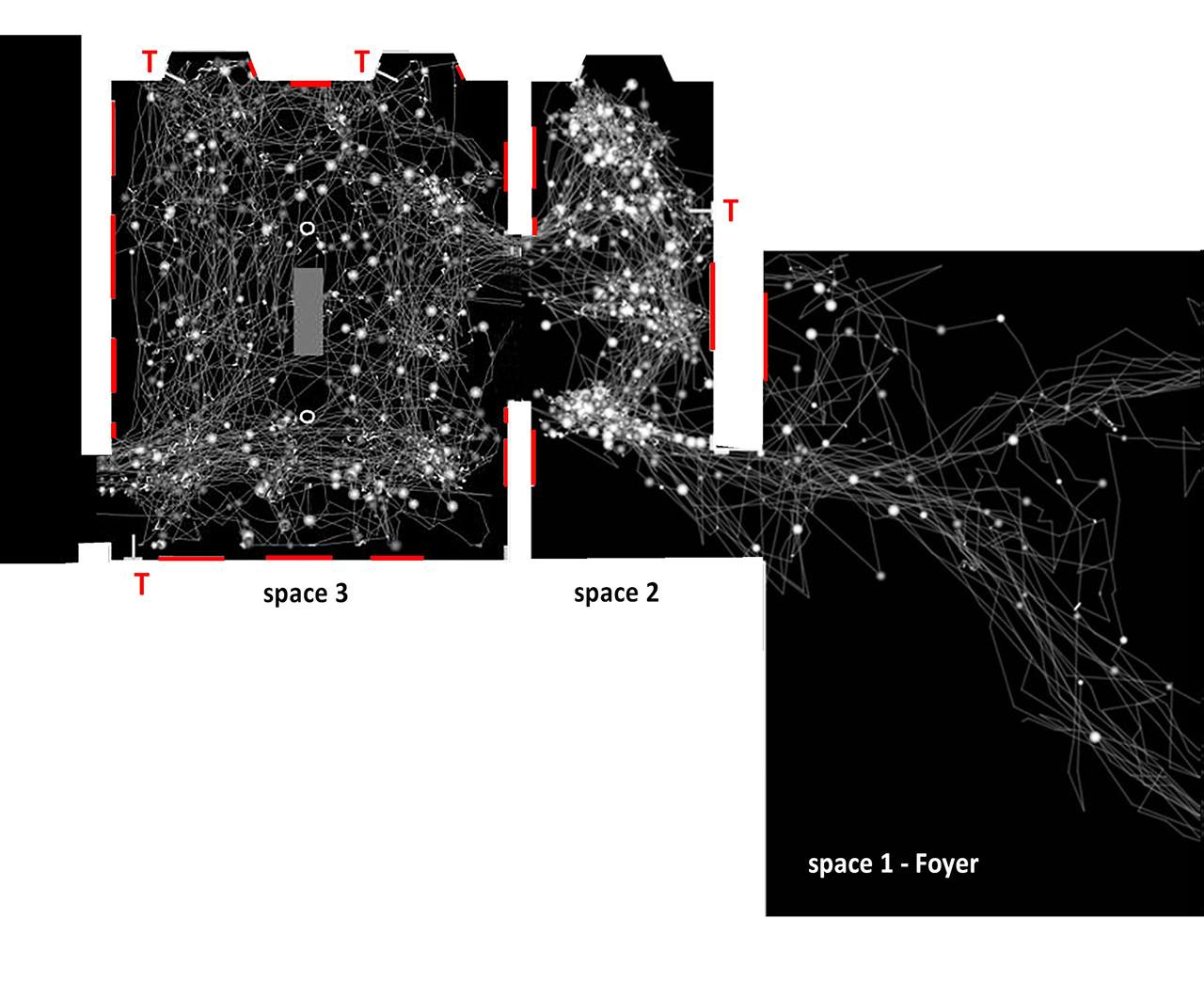

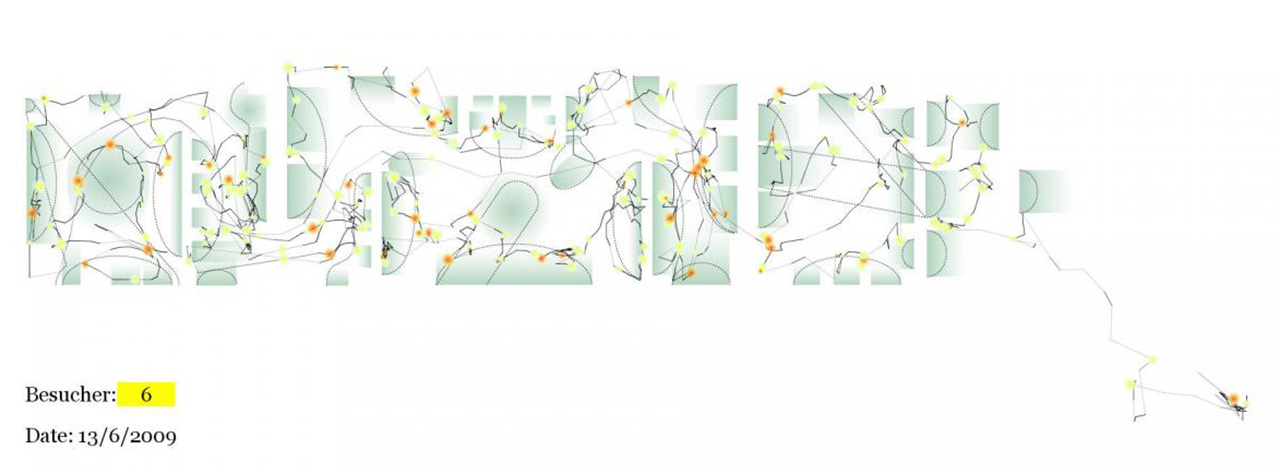

The 552 visitors who agreed to take part in the project wore a specially manufactured sensor-glove during their museum visit. The glove provided the research team with data on the path taken by each anonymised participant, (with a precision of 15 cm) as well as two physiological parameters: heart rate (HR) and skin conductance level (SCL). The data-sets obtained by the glove culminated in a series of stunning maps that show direction, speed, pause duration and physiological response. This data, combined with results of an entry and exit survey, allowed researchers to observe cognitive and emotional response patterns to the artworks in relation to the physical environment within which they were contained.

Reading the maps:

The maps produced for the eMotion experiment are extraordinarily beautiful, eloquent and immediately recognisable as representations of our own experiences. Each line on the map represents the presence, or absence of a single person’s thoughts, feelings and actions. The combination of lines forms a complex set of illustrations that highlight the difference between the common experiences that we share and those that are unique to each individual.

No two experiences are exactly the same, but the rhythm of pause and movement begins to reveal some common patterns.

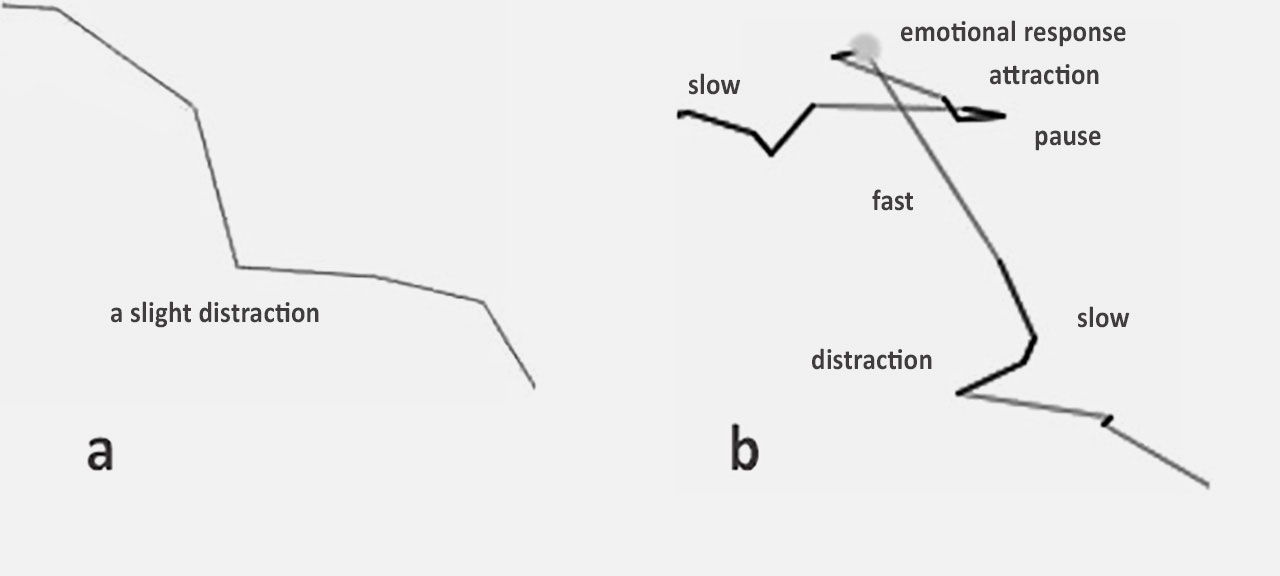

The density of these lines indicates the speed at which a visitor moves, the fainter the line, the faster the visitor is moving (Fig.03a); when the visitor would come to a standstill the line darkens (Fig.03b). This is clearly observable when taking a closer look at a single visitor path. The location was tracked every second – for each second a point is plotted and for the cartographies, a line was drawn from point to point. As such, the faster a visitor moved, the longer and straighter the line points in one direction; conversely, a ragged, short-lined path indicates slower movement.

What does it all mean:

These findings point to a significant link between physiological responses of visitors and their subjective, aesthetic-emotional evaluations. More importantly, the implications of this research extend far beyond the walls of the gallery, out into the streets of our cities and the places in which we work, learn, shop or play. Trondle and his team demonstrates the effectiveness of sensor-based mapping technologies, to help us understand more about human behaviour and our response to objects of interest, within any given context.

We may be justified in our concerns about the potential abuse that can occur when surveillance technologies are deployed without the knowledge or consent of the people being observed—potentially all of us. Such technologies may have been used effectively in the fields of criminology and international espionage, but perhaps it is time that we broadened that thinking to the everyday world that most of us inhabit.

In the mid-twentieth century, the behavioural sciences sought, and failed, to manipulate human behaviour to fit into pre-determined environmental models. Today we have the capacity to turn the process on its head, using new tools to improve our knowledge of human behaviour, so that we can design better environments to support our needs and desires, and not the other way around. The tools used by Martin Troendle and his team will allow us to accurately study anthropospatial transactions in all their splendid complexity—a task that until now has been too complicated and too expensive to undertake with any degree of rigour. These maps tell a different story. They speak of unlimited possibilities.

THE EXPERIMENTS:

The article reviewed for this post is one in a series that has come from the Swiss national research project eMotion –mapping museum experience. eMotion is a five-year research project which analyzes the museum experience experimentally, involving scientists from various fields, technicians, artists, and practitioners.

In this article, the researchers investigate if and how curatorial and spatial arrangements have an impact upon visitor attention. According to the principle investigator, Dr Martin Tröndle, this question is rarely dealt with in the field of museum studies, the literature to date having primarily focused on the historical development of displays—one reason being the complexity of the behaviour involved. In fact, this research project was only made possible through the development of highly accurate position-tracking combined with high-speed computers to process the enormous amounts of data involved.

The eMotion research project has generated numerous findings over its five years, but this post concentrates on four significant outcomes that shed light on the ways in which physical space can affect the way we respond to works of art.

1: Outside-Inside

Q: Does the location of an artwork ‘outside’ the official exhibition space have an impact on the degree to which a visitor will engage with it?

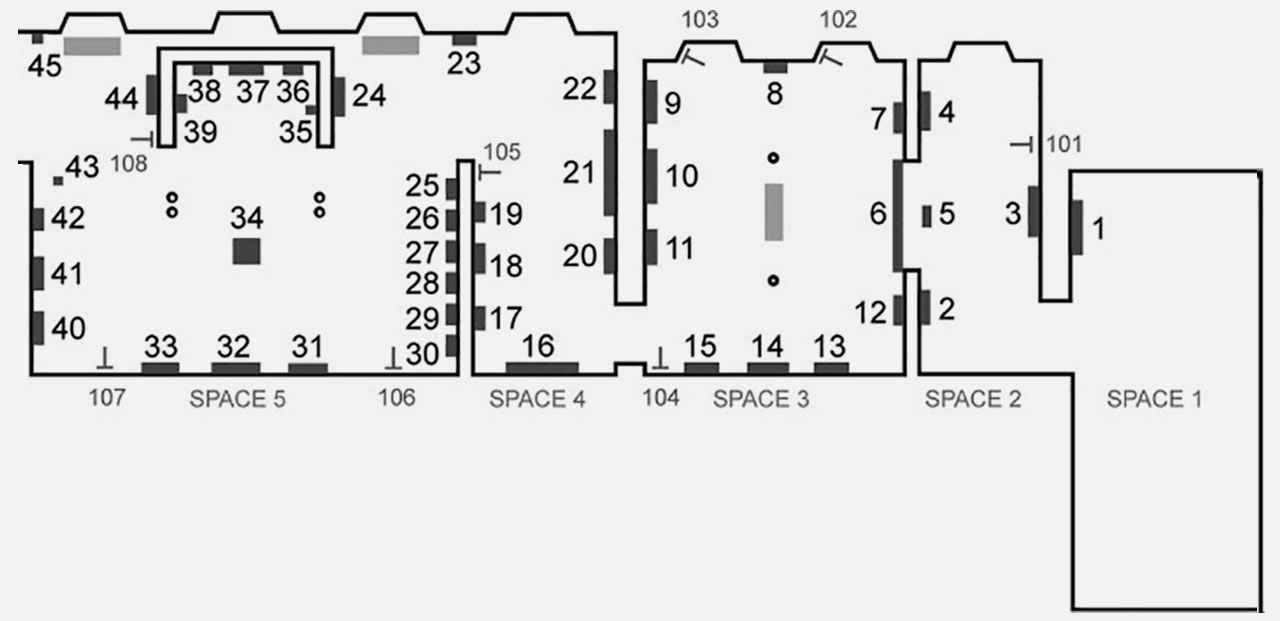

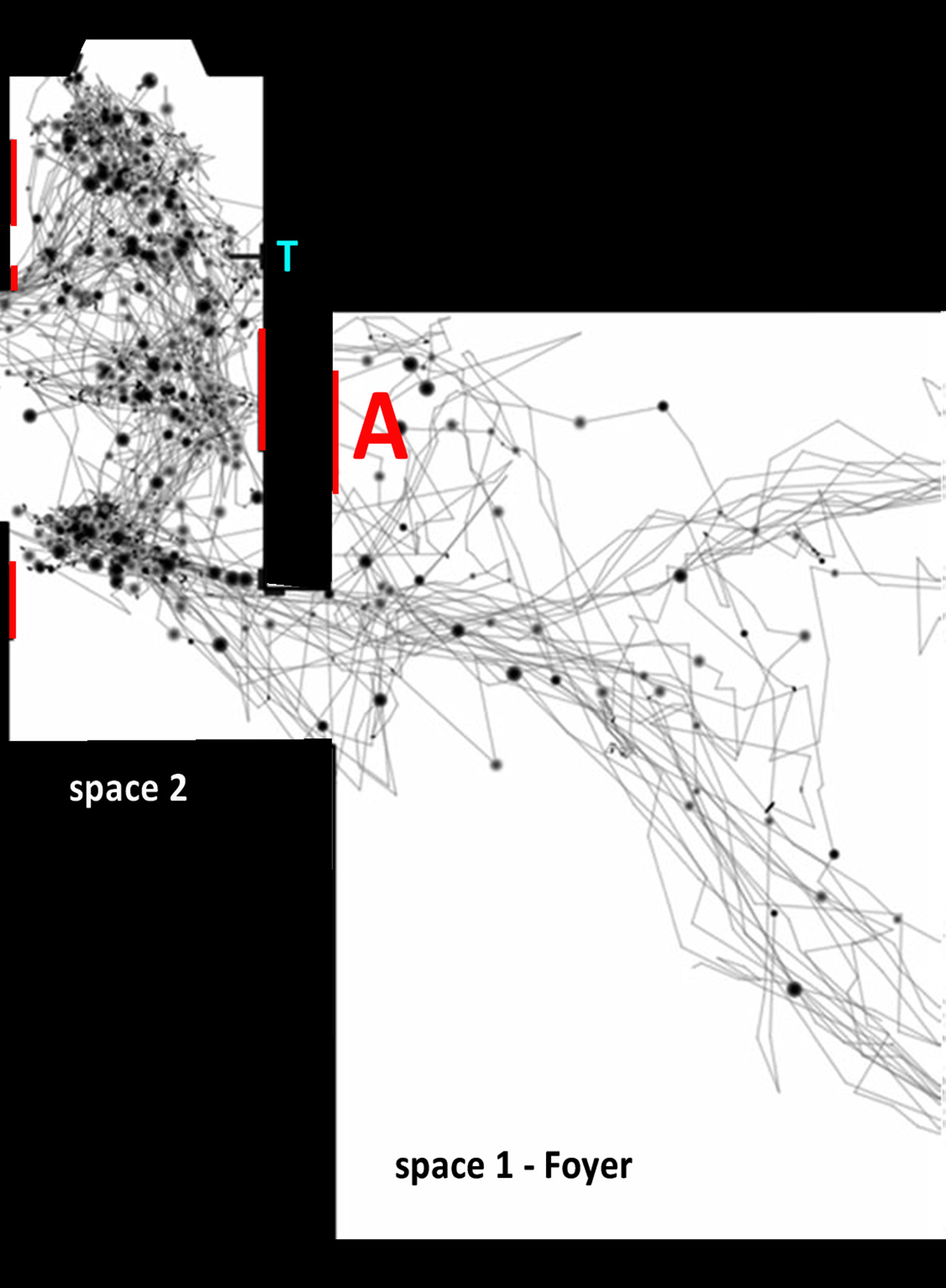

In this first experiment, a normally popular painting was hung in the foyer space of the museum, before the official entrance to the ‘actual’ exhibition (Fig.07, Location A). The painting was changed often and it was also removed completely. The entrance was clearly distinguished by curatorial signage and a change in the wall colour (Space 2 is painted a bright yellow), a defined opening and a change in floor surfaces (wood floor).

Findings:

The research team found that visitors crossing the entrance hall display only very minor heart rate variability but as soon as they enter the first, smaller exhibition hall (Space 2), their physiological reaction rapidly increased. It made little difference what painting, if any, hung in the foyer, or whether that work was figurative or abstract. From fig. 07, it can be clearly seen that visitors did not linger in the foyer, while works contained within space 2 were observed more closely.

It is clear to Martin Tröndle that: “the cause of increased attention does not lie in the phenomenology of the artworks. Instead, attention is dependent on whether artworks occupy a particular position, such that they are perceived to be part of an exhibition… only when the visitors enter into a different viewing mode is the aesthetic experience intensified.” It can be inferred from the maps generated during this experiment, that our personal intentions, to visit a particular event, can create a series of expectations that diminish our curiosity about the world beyond that purpose.

2: Series?

Q: Can works in a clearly related series can attract more attention than groups of unrelated works?

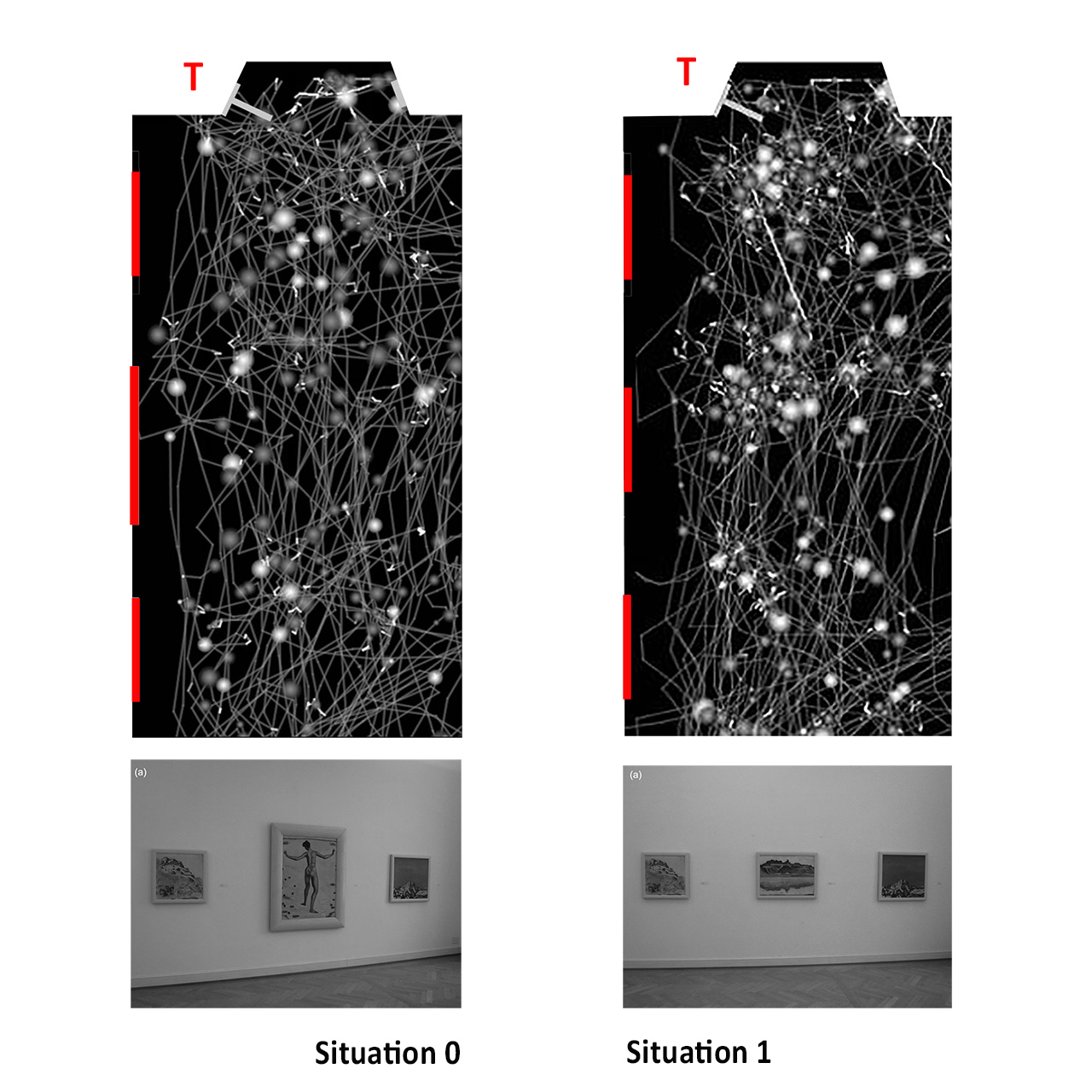

For the first arrangement (Situation 0), Ferdinand Hodler’s Beauty of Lines, depicting a female nude, was positioned between two of his mountain landscapes. The nude dominated the landscapes, as it is larger in size. In addition, the comparatively large nude hung directly in the visitor’s line of sight upon entering the room.

In Situation 1, the nude by Hodler was replaced by his mountain landscape, Thunersee mit Stockhornkette, to test the effect of what is known as a single-line hanging.

Findings:

Situation 0 evoked a rather diffuse visitor attention, and the visitor reaction is less pronounced than it is compared to the other artworks in the same room.

Situation 1 resulted in recognizable centres of observation. Visitor paths became tangled as they paused to inspect the artworks more intensely. The rearrangement evoked a noticeable difference – the opposite of the expectations from the curators.

3. Corners?

Q: Does the location of an artwork within a designated gallery space affect the degree to which visitors engage with it?

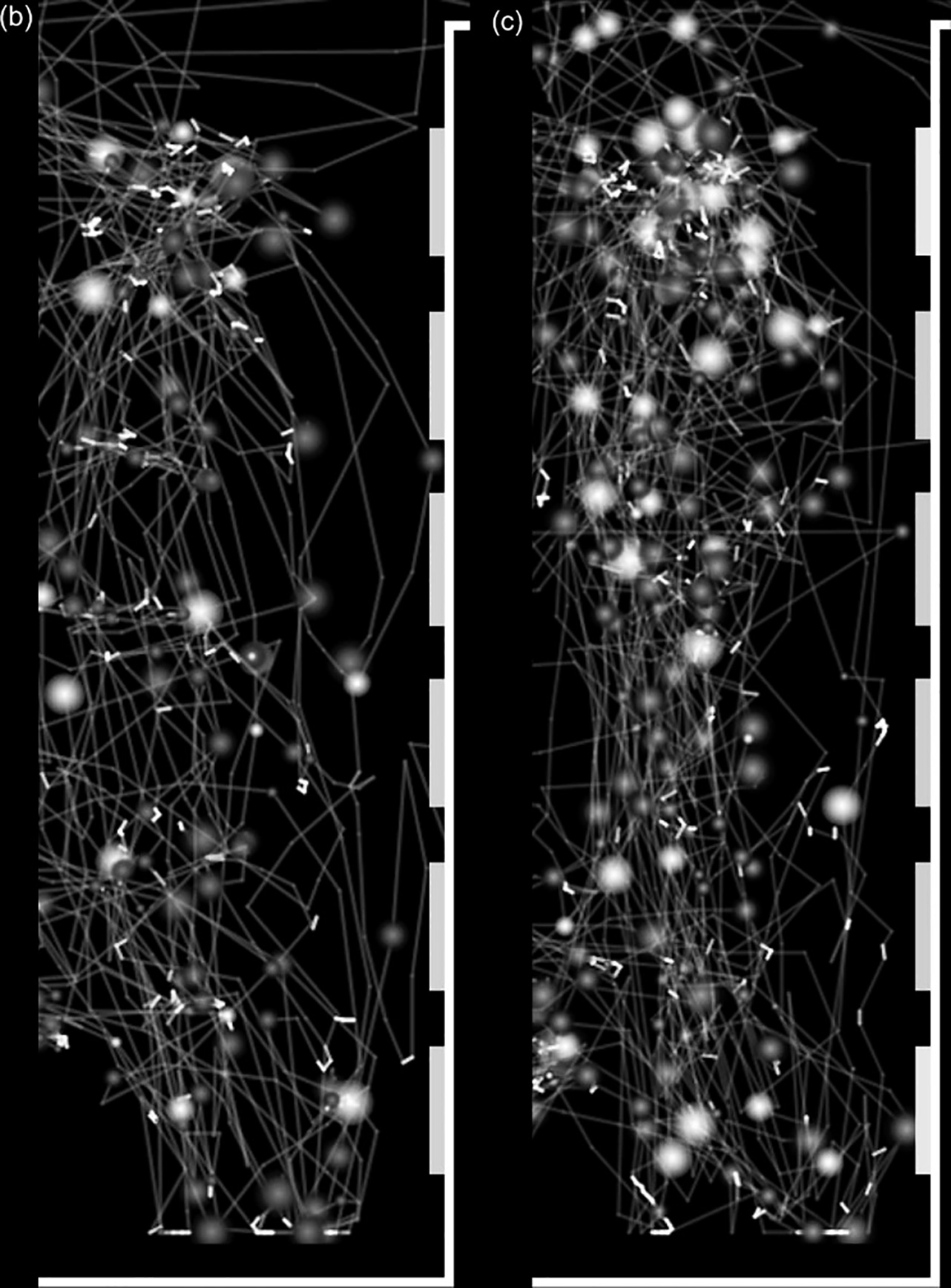

In Situation 0 (fig.08), Hodler’s painting Beauty of Lines was approached 207 times (for more than three seconds) and it was examined for an average of 12 seconds (Total 2,424 seconds). Giacometti’s painting Farmer on the Fields at Maloja was approached 75 times and examined for an average of 10 seconds (Total 782 seconds).

In order to clarify the extent to which the attention attracted by Beauty of Lines was a consequence of its central placement in the room, an additional arrangement was carried out. For situation 1, the artwork (Beauty of Lines) in front of which visitors remained the longest in this space, was exchanged with the artwork in front of which visitors spent the least amount of time. Beauty of Lines was moved to a corner position and Farmer on the Fields at Maloja was changed to a central position (Figure 9a and b).

Findings:

Exchanging the two artworks had little effect on the observation time and frequency related to Farmer on the Fields at Maloja…By contrast, the rearrangement caused considerable variation in the reception of Beauty of Lines. While this artwork was observed for the longest period of time in Situation 0 (total duration of 2284 seconds), the corresponding total observation time in Situation 1 was calculated at a mere 134 seconds. The number of visits decreased from 207 to 17, and the observation time per participant fell from 12 to 8 seconds! The attention attracted by Beauty of Lines at its new position in the corner, quite literally, dissolved.

4. Repetition

Q: Does the order in which individual works in a series are displayed have an effect on the degree to which people engage with them?

In this setup, six small works by Julius Bissier were swapped around in four different ways to see if location of a particular piece within a single-line hanging.

Findings:

Referring to fig.10, regardless of content, the first artwork (upper right on the figure) and, to a certain extent, the second artwork were examined by visitors in detail. Thereafter, visitor interest began to dwindle and grew weaker along the row, independent of the hanging order.

According to the research team, highly similar visitor behaviour was observed in other situations where artworks were displayed in a row. One can infer from these results that, where the objects of attention are similar to each other, people tend to feel that no further investment is required beyond the first or second object.

METHODS:

The researchers noted that the visitor behaviour in a museum or gallery is not just dependent on the curatorial context, the artworks, and the architecture, but furthermore on the interactions of the museum visitors themselves and how many visitors are present in the exhibition halls. The museum was not particularly crowded during the study. Altogether, 1881 people visited the museum between 5th June and 16th August in 2009, approximately 30 visitors per day. This moderate visitor number permitted undisturbed viewing conditions.

As visitors bought their entry tickets to the Museum, they were asked if they would consent to participate in the research project. Subjects were required to be 18 years or older; not to have previously participated in the eMotion project; to be a lone visitor or in small groups (no guided tours); and to be proficient in German or English. The 552 visitors who agreed to take part in the project received a sensor-glove that they wore during their museum visit.

The data-sets generated by the apparatus were complemented by a standardized visitor survey filled out before the visitor entered the exhibition (‘entrance survey’) and an individualized survey following his or her visit (‘exit survey’). In order to test this data, a control group without the glove answered the same surveys. The two groups with (n = 552) and without (n = 24) the glove were compared by variance analyses, to see if the visitors without a glove responded differently. All in all, the influence of the glove on the survey results was found to be minimal. Altogether, 3555 single assessments of artworks were collected during the course of this study.

CONCLUSION:

The findings of this research pointed to a significant link between physiological responses of visitors and their aesthetic-emotional response to the artworks—and this in turn affected their spatial behaviour in a measurable way.

According to Martin Tröndle , exhibitions cannot be considered solely on the basis of objects and meanings, or by situations and settings in isolation of each other because they are “complex networks of actions and force fields in which a rapport between visitors, architecture, and things can be generated... It is not sufficient to focus one’s study on the supposedly self-determined, autonomous subject that intentionally ‘consumes’ exhibits… or the passive observer who allows an exhibit to ‘transmit impact’… Instead, it is necessary to take into account what takes place within the network of interactions where attention is fostered, directed, and redirected within the museum environment.”

Dr Tröndle concludes that, although the influence of position on the reception of an artwork is not to be underestimated, dominant artworks are not able to organize the ‘force field’ of the exhibition space around themselves from every position in the room. Rather, based on the experimental findings presented in this paper, the influence of a particular work appears to be possible only from particular locations.

The implications of this research extend far beyond the limitations of this particular project, in terms of our ability to collect data about public behaviour in any performative environment. However, there are also implications for the ethical collection of that data in ways which do not diminish the rights of the participants involved. Much discussion and public acceptance is required if we are to be ready for an immediate future, one where we will tread a fine line between the benefits of previously unattainable knowledge, and the protection of our personal privacy.

REFERENCES:

Connect to Tröndle et al, 2014 The Effects of Curatorial Arrangements. Museum Management and Curatorship here

For further information on the eMotion project and publications visit here

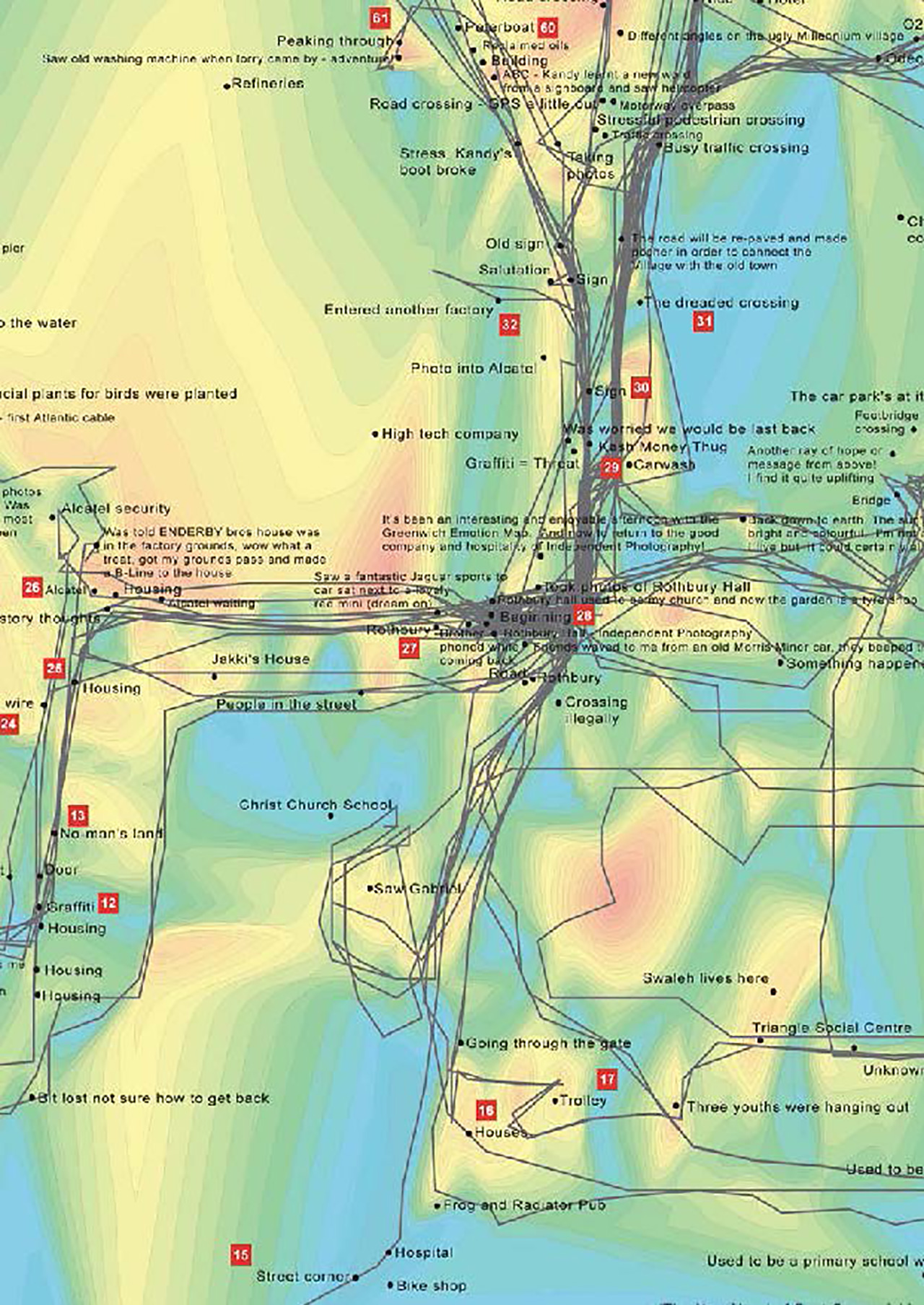

To download Christian Nold's paper on the Emotional Cartography experiment--similar, but not related to the eMotion experiment--visit here