What do we find most attractive about a new job offer? How important is the physical workplace in that decision-making process? A recent Australian study, undertaken by Hassell Architects and Empirica Research, dug up some intriguing stories about the role of workplace culture, people and design in the decisions we make about where we will spend ours days.

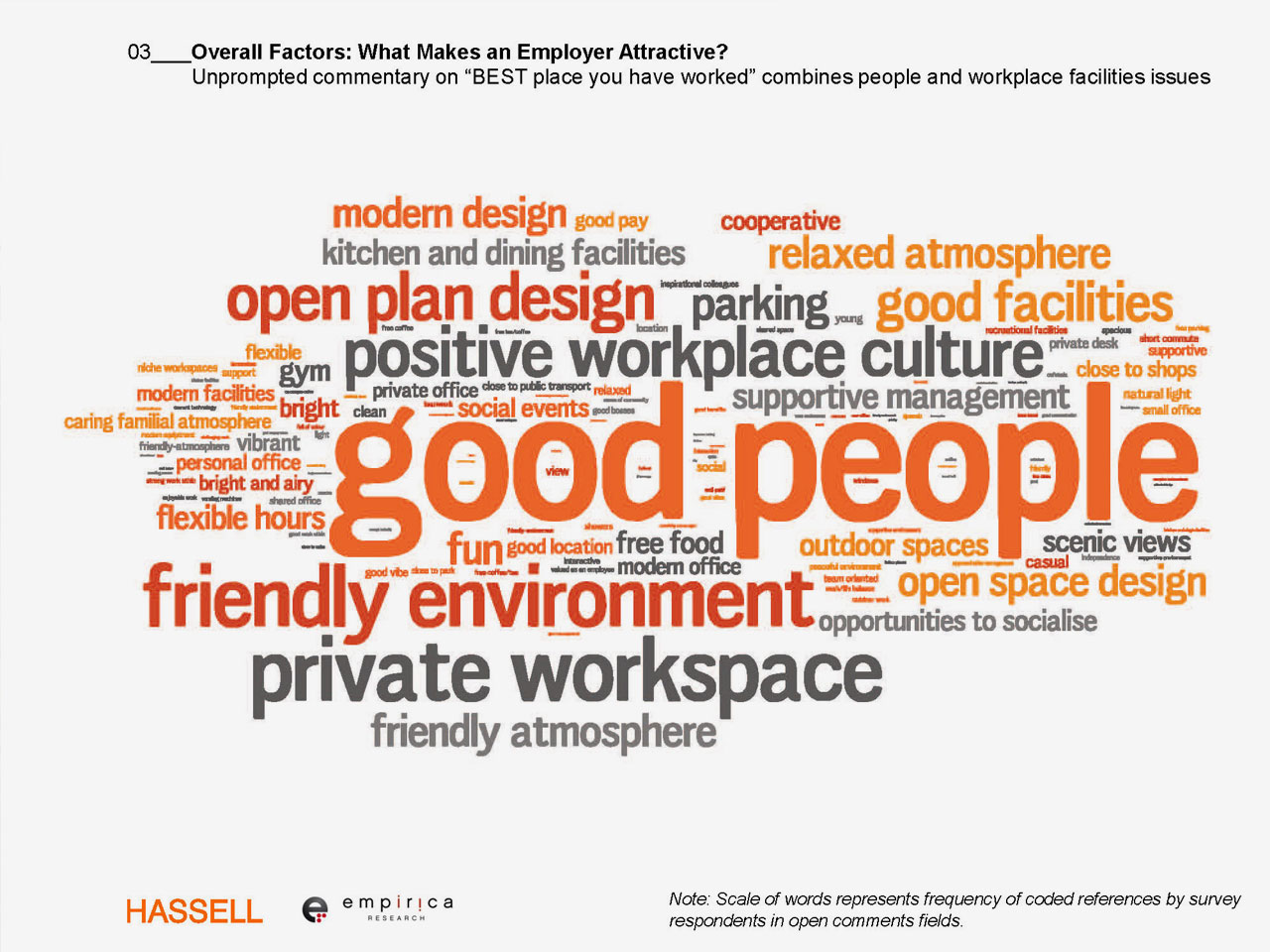

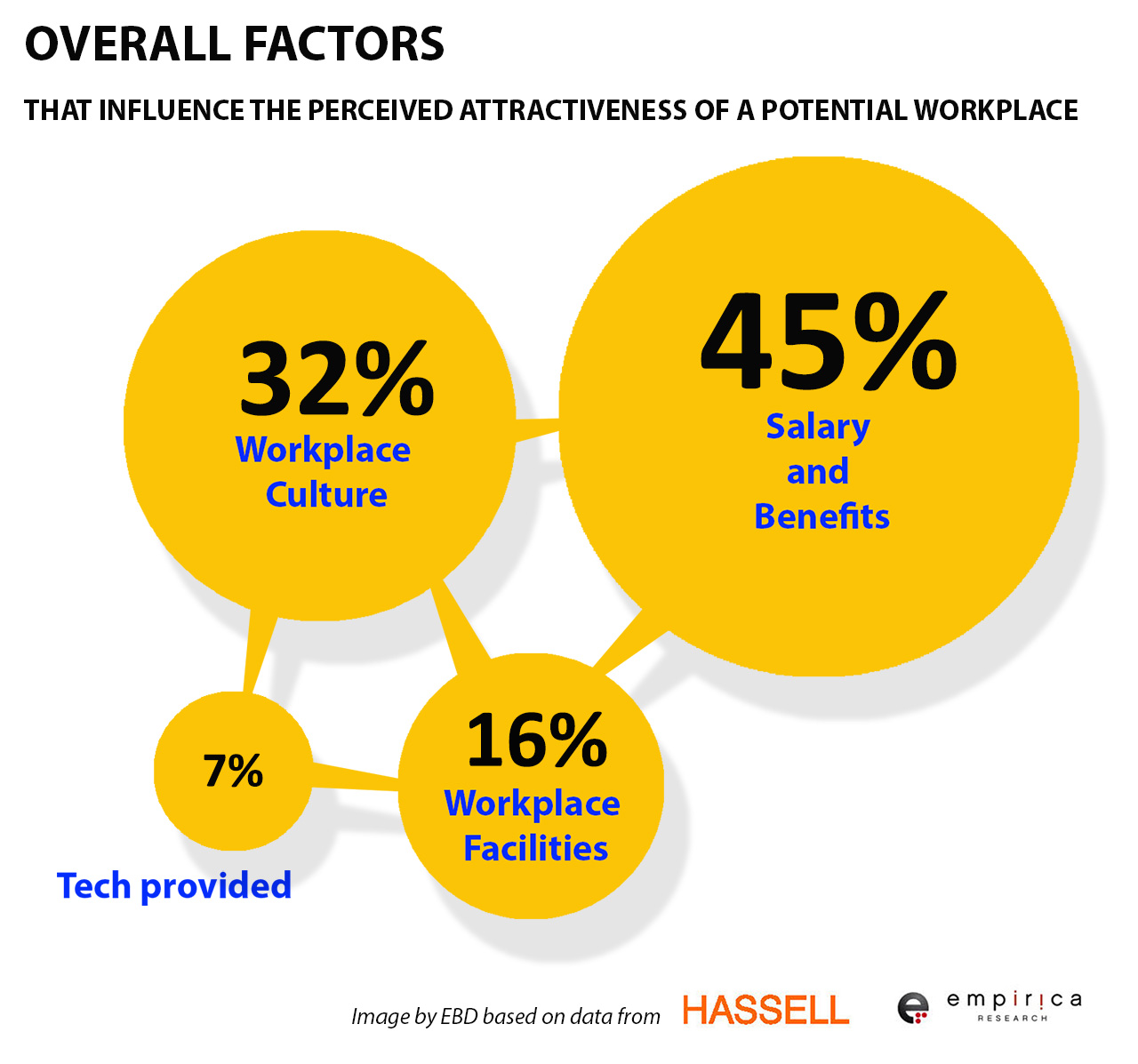

In this recent pilot study, 1000 un-primed survey participants were presented with a series of hypothetical job offers and were asked which job they would prefer. Despite what appears in the cloud of open comments above(fig.01), almost half of respondents (45%) placed salary as the most influential factor in their decision to take a job or not. (fig.02)But that is not the whole story.

According to the survey, 32% of respondents found workplace culture to be a primary influence on their decision. For 16%, a significant proportion of the sample, their decision was most influenced by physical workplace conditions (fig.02). Interestingly, work technologies were the least attractive factor (around 7%).

Put simply, when combined, workplace facilities and culture can exceed the lure of money.

The apparent difference between the open comments of the cloud, and the response to multiple choice questions, is partially explained by the limitations of the online questionnaire as a research tool—but that does not negate the value of this pilot study. Not only do we gain a preliminary insight into the priorities of potential employees (at least those who participated in the study), but there are also implications for the retention of existing employees.

What does it all mean?

Steve Coster 1, head of the Commercial and Workplace division at HASSELL, suggests that although the physical environment may not be the most significant attractor for employees, it is still a significant stimulus that should not be underestimated. "This study is the first step in a process that helps us to articulate the commercial value of design" said Mr Coster, "We can show that the expression of identity, through design, has a significant role to play in attracting new talent to an organisation." He also maintains that, beyond the limitations of its content, the study has had an impact on HASSELL's practice methods: "We are becoming more structured and specific in our discussions with clients, as we substantiate some our ideas with point facts, without losing the immeasurable qualities that also make a design work".

As always, further more detailed research is required, but this study adds to a growing body of knowledge,23 while laying the groundwork for more detailed analysis. It would be particularly worthwhile to focus on what place qualities might also affect our perception: Light, view, air, volume, sound, etc. but that would take a much deeper and broader piece of work over a prolonged length of time.

Details

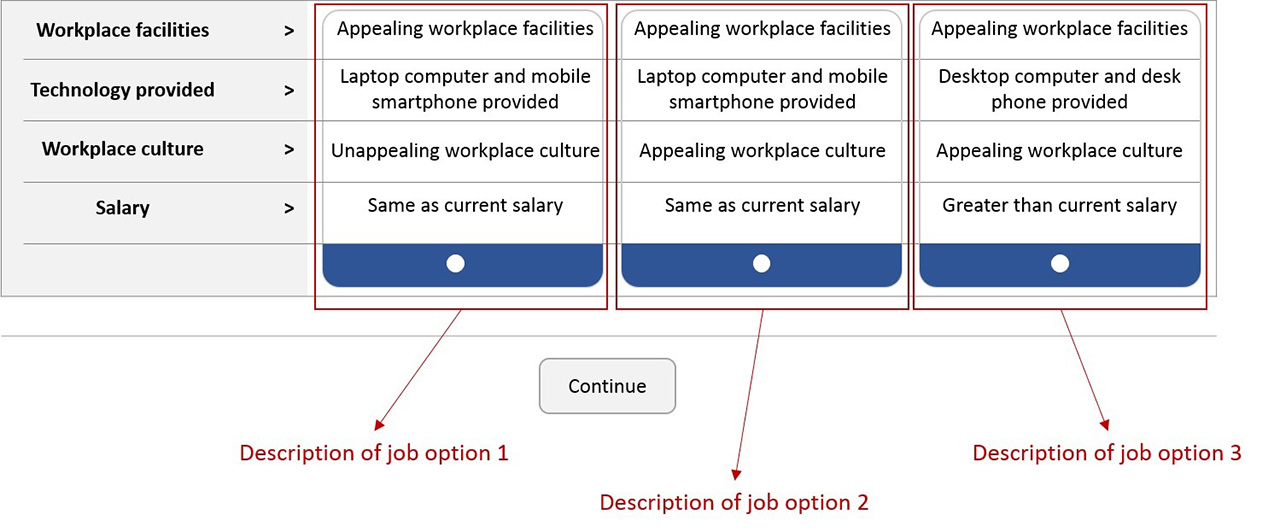

Survey participants were presented with a series of hypothetical job offers and were asked which job they would prefer—first, in the context of four qualifying factors: workplace facilities, technology provided, workplace culture and, finally, salary and benefits. (Task 01)

Participants were then asked to select a preferred job based solely on factors specific to the physical workplace: Layout, Aesthetic and Additional facilities (Task 02).

Choice Task 01: Preference Qualifiers

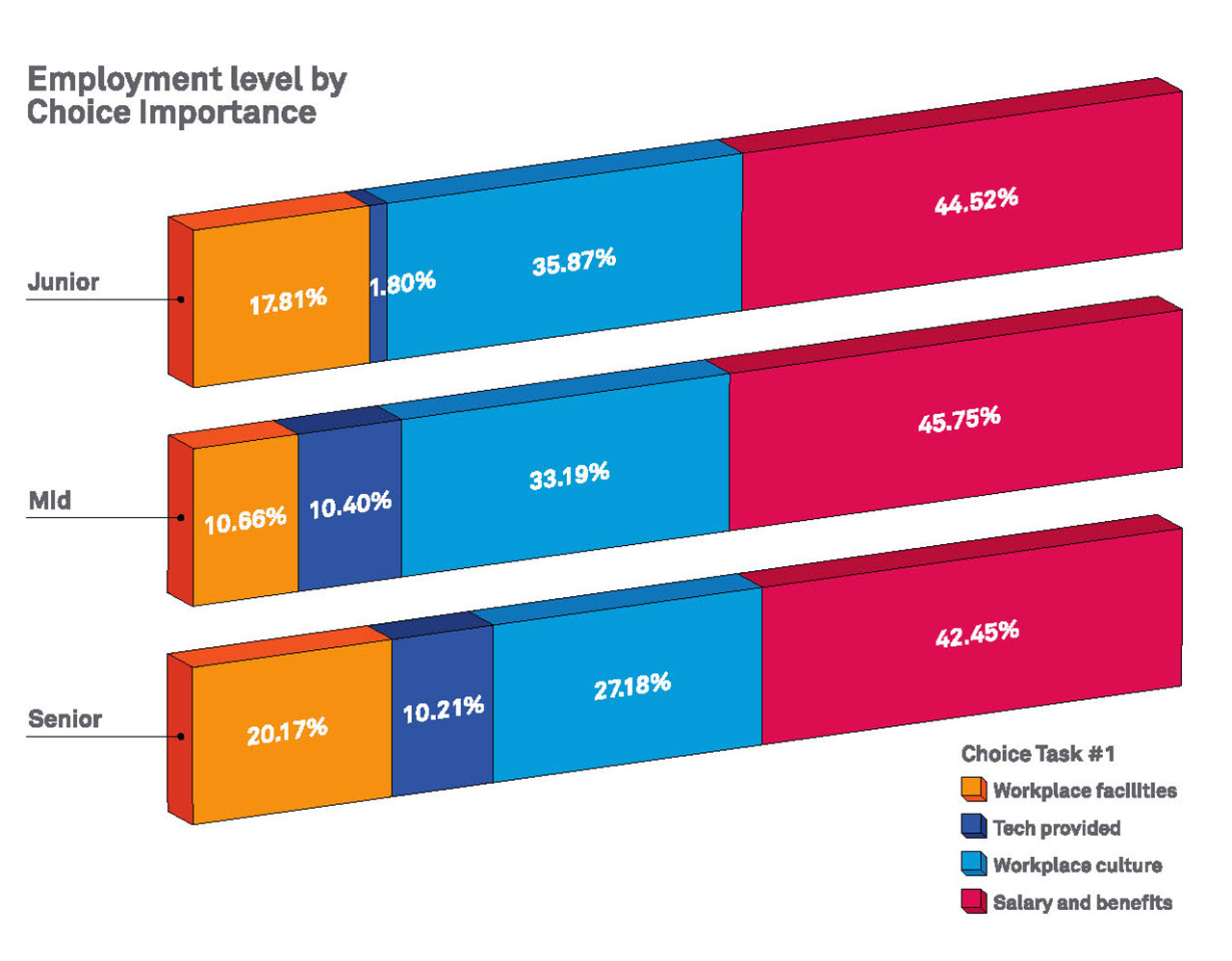

Interestingly, younger people were less attracted to the provision of technology (2%), placing a greater emphasis on culture (36%) and physical workplace (18%).

Technology becomes more important to mid (10%) and senior level respondents (10%), however, workplace culture becomes less important to senior staff (27%), representing a drop of 5.5% from the norm. (fig.03)

The results indicate that the physical workplace plays a more significant role in the decision-making process for junior staff (18%) and senior staff (20%) than it does for mid-level staff (10.5%)

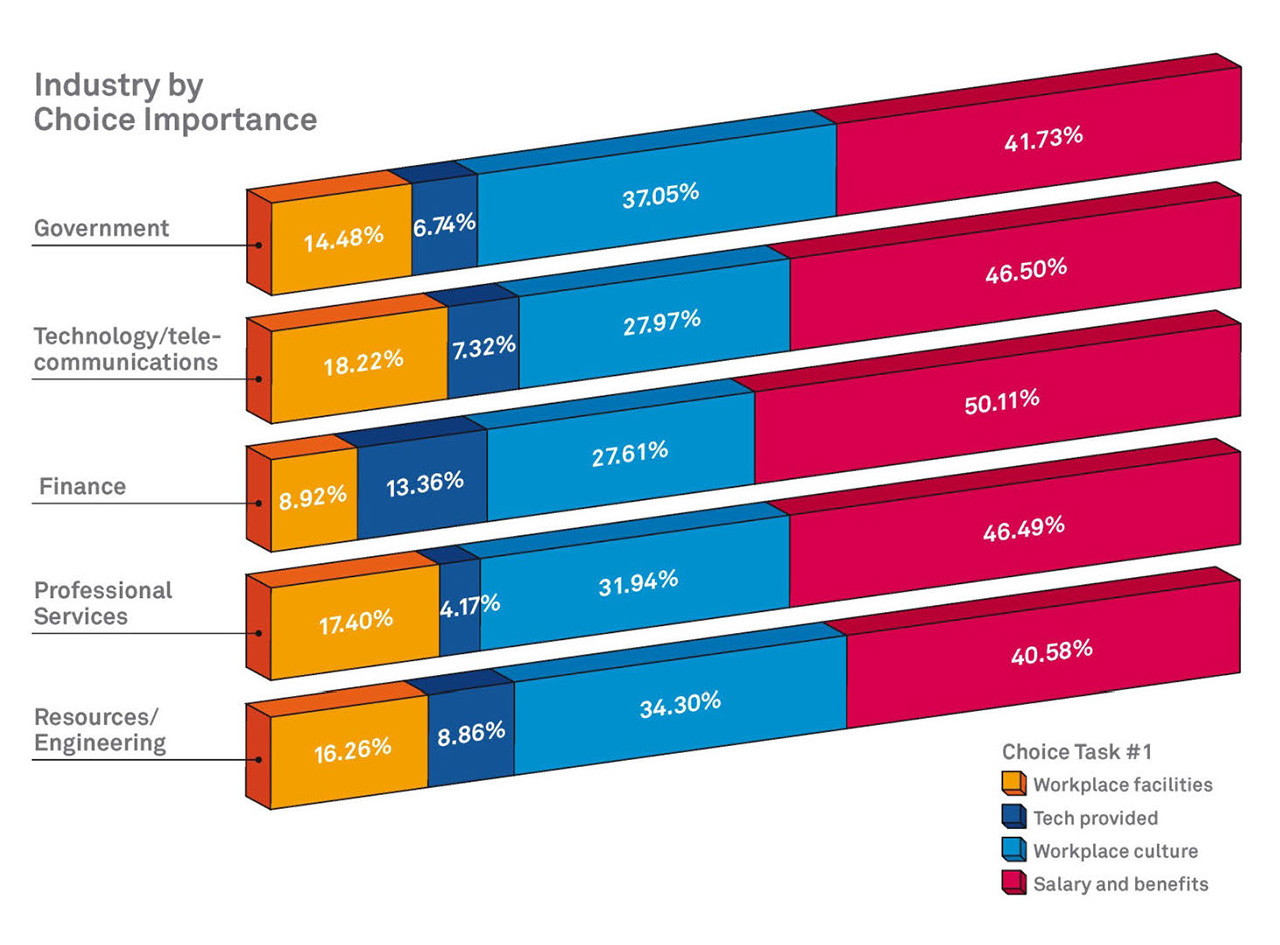

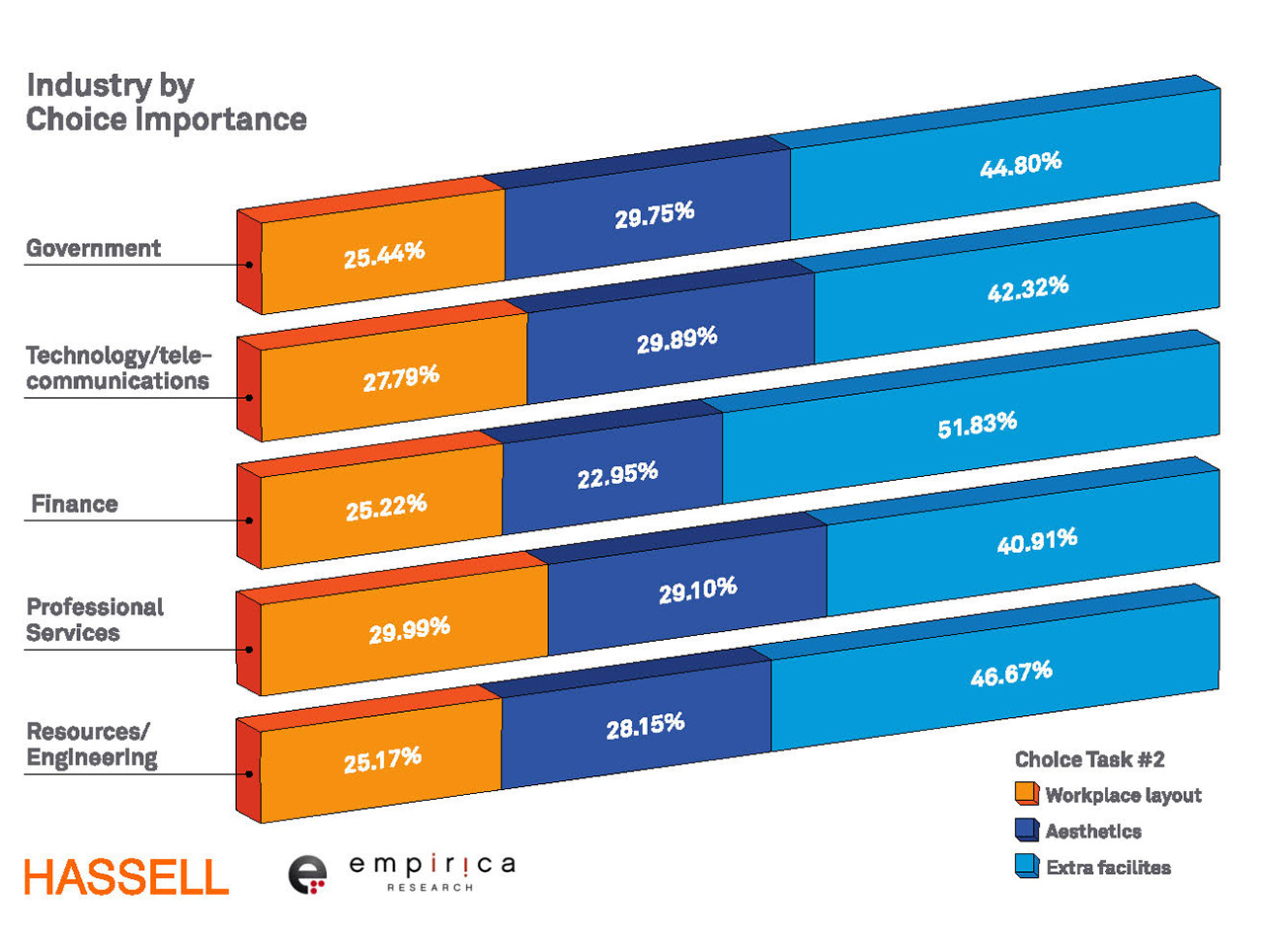

Across industry sectors the study found that workplace is MORE important for the Technology, Professional Services and Resources/Engineering sectors that it is for the Finance Sector, where technology is a more significant factor. (fig.04)

Choice Task 02: Workplace specific factors

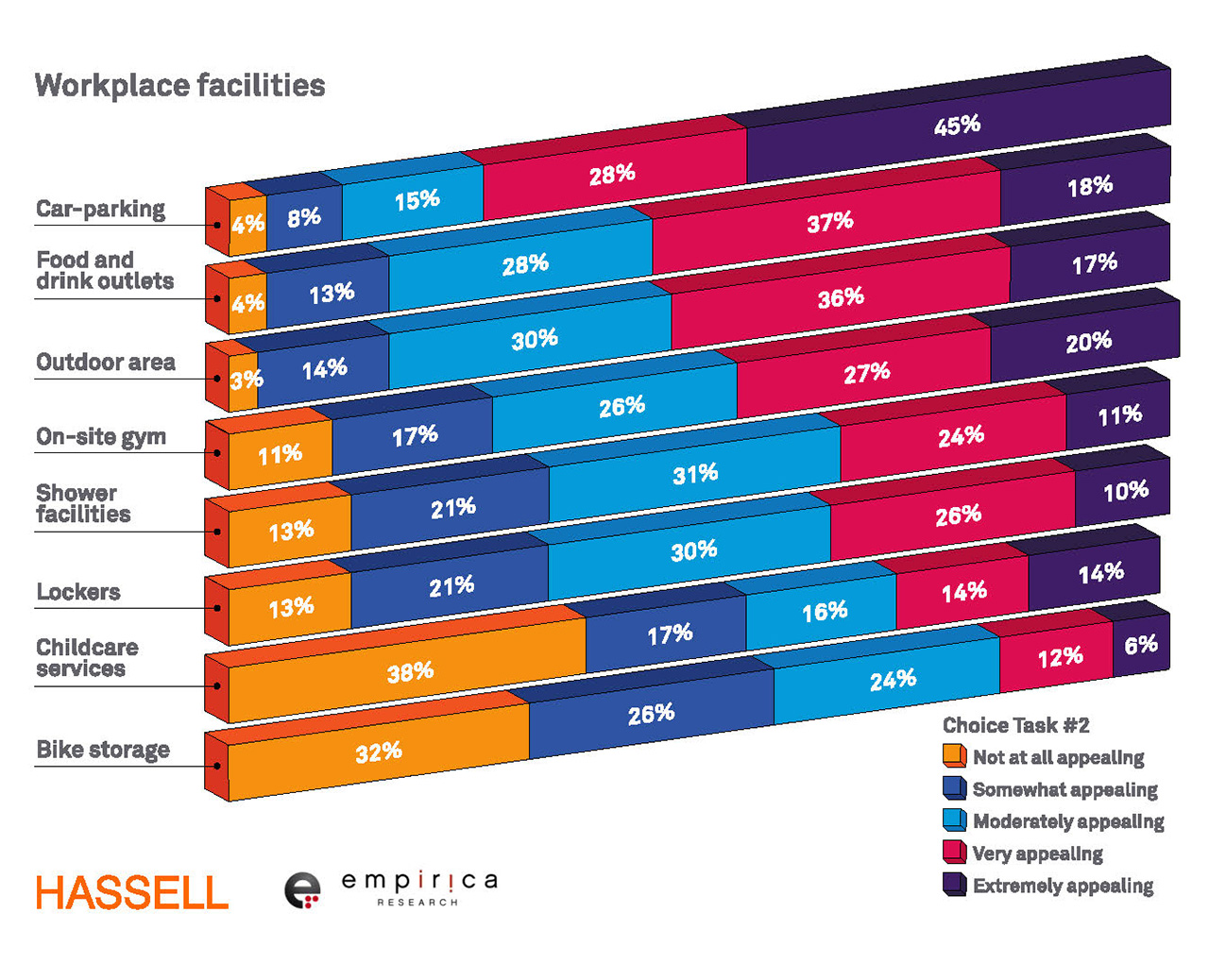

When asked about workplace-specific factors, independent from salary, 44% of respondents found the provision of extra facilities to be more influential that aesthetics (29%) or layout (26.5%) (fig. 05). In terms of extra facilities, 73% of respondents found the availability of car parking to be very/extremely appealing, while the provision of food and drink outlets, outdoor areas and an on-site gym had similar appeal at around 47%-55%. Interestingly, although often assumed to be of high priority to staff, the provision of childcare and bike storage had the least appeal to respondents.

The importance of workplace aesthetics, over layout and facilities, was found to be reasonably similar across industry sectors, gender differences and levels of seniority, although less so in the finance sector where extra facilities were considered to be significantly more important. (fig.06)

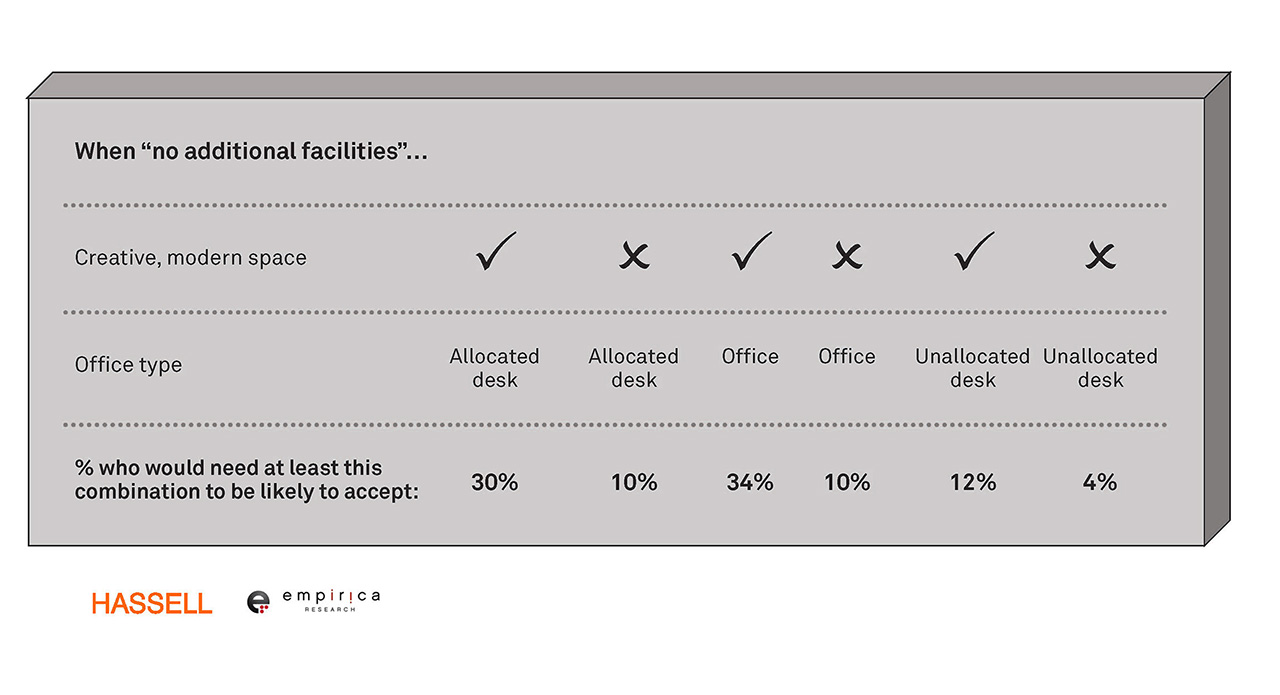

When the provision of additional facilities was removed from the decision-making process, the importance of aesthetics becomes more apparent. Respondents were three times more likely to accept a job offer if it included a creative, modern workplace than if it did not. (fig.07) Unallocated desks were found to be the least popular quality, but again, the attractiveness of the offer was three times stronger if combined with an attractive work environment.

Methods & Limitations

Data were gathered from an on-line sample of 1000 people who were un-primed (i.e. not informed as to the purpose of the survey). To determine the relative importance of different features of a job, respondents were asked to complete two sets of conjoint analysis choice tasks. Rather than just asking respondents what feature is most important to them in accepting a job, conjoint analysis uses more realistic trade-off situations.

Respondents were asked to complete a series of choice tasks in which they selected their most preferred job from different hypothetical job offers. (fig.08) By independently varying the combination of job features that was shown to respondents for each choice task, the researchers were able to statically determine which job features were the most important to respondents.The intention of this method is to reduce bias caused by respondents seeking to provide what they feel are ‘correct’ answers.

Respondents were balanced for Gender, Location (Sydney, Perth, Brisbane, Melbourne), Age (18-66 or older) and 5 Industry sectors (Tech/tele, Gov, Finance, Professional services, Resources and Engineering.

Other factors taken into account included Employment type, employment status, salary, experience and education. All respondents were either currently looking for a new job or had just started a new job.

Perhaps the biggest methodological limitation of the research was that the researchers were unable to determine how respondents imagined the workplaces being described. For example, workplace facilities and workplace culture as described in the first set of choice tasks is likely to have been informed by respondents’ personal experiences and, therefore, may have been interpreted differently across respondents.

As a single study, limited to Australia, the findings are not generalizable or applicable for other parts of the world. However, that does not diminish the value of this work as a useful pilot study in this area. To address this limitation, Hassel and Emprica Research have conducted subsequent research with respondents from Hong Kong, London, Shanghai, and Singapore. (This research will be presented in future articles-Ed)

-

Steve Coster, Principal at Hassell linkedin.com/pub/steve-coster/4/302/a12 ↩

-

Bodin-Danielsson, C. and Bodin, L. (2008) Office Type in Relation to Health, Well-Being, and Job Satisfaction Among Employees Environment and Behavior 40: 636 DOI: 10.1177/0013916507307459 eab.sagepub.com/content/40/5/636.abstract ↩

-

The Impact of Office Design on Business Performance, British Council of Offices, 2006 webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110118095356/http:/cabe.org.uk/files/the-impact-of-office-design-on-business-performance.pdf ↩