Spacelab is a UK based Architectural Studio that has been at the forefront of evidence-based design for almost two decades. Most recently Spacelab were voted best Interior Design Practice of 2018, in the FX awards. Dr Darragh O’Brien caught up with one of their Directors, Rosie Haslem, at their London studio. The following is an edited version of their conversation.

The Takeaway:

- The London Based studio, Spacelab, has been using data-based research methods for over 17 years, to inform the way they engage with their clients and design bespoke workplace solutions.

Darragh O'Brien is the founding Director of EBD. - Spacelab use software developed with the Bartlett School of Architecture to model the impact of potential design interventions.

- Their latest adventures have been in the use of Augmented Reality (AR) tools to gauge occupant response and gather data during the design process.

EBD: Spacelab has been in practice for almost two decades now. Can you tell us a bit about the early days and the basis for its inception?

RH:

Spacelab was founded on the principle that architecture should be approached from the inside out—that great design starts and ends with people—and seventeen years later this principle still defines our purpose, driving every decision and direction that we take. By connecting research, technology, and creativity, we have taken a progressive approach to data-driven design, to create spaces that bring out the best in people.

We have brought this philosophy to a wide variety of exciting projects and forward-thinking clients: from Great Ormond Street Hospital and Goodwood Racecourse to community developments and FTSE 100 companies. We work closely with our clients to help shift their way of thinking about space and people, and our research helps us to do that.

EBD: You argue that research underpins all of your design activities. Can you elaborate on how those systems are connected?

RH:

We started pioneering an evidence-based approach to our ‘workplace consultancy’ and design process from the very beginning. Working in collaboration with the Bartlett School of Architecture at the University College London (UCL) 1we implemented methods such as workshops, interviews, online surveys and observations. While these methods have become, to varying degrees, standard within the industry, we’ve pushed our approach even further - asking new questions and developing new solutions – which gives us a deeper insight into the social and spatial functioning of a business and their people. We can now tailor each project’s process specifically to the client, helping us to develop and deliver human-centred design solutions that really work for their unique needs.

As for the integration of research and design, each project team consists of a researcher and a designer who collaborate throughout the whole process, integrating the analytical and the creative. They work together to unearth the problems and challenges that a client is facing, both organisationally and spatially, and develop tailored solutions for these problems.

Our collaborative research approach also extends to how we work with our clients. We identify a cross-section of users early on in the project, who act as representatives of the various teams and users of the space, and who we then work closely with throughout, gaining their feedback as we go along in a connected and iterative process.

EBD: Can you tell us a bit more about how you do that?

RH:

Our proposed design solutions are modelled within a VR environment and then tested by users to inform iterative ‘cycles’ of development. For example, a receptionist can sit at their desk to see if they have the necessary visibility of new arrivals, whilst in a retail business, a designer can test their accessibility to products and samples, as well as proximity to various teams that they work with frequently. Users identify issues and inform solutions, and through this engagement we often generate new avenues to explore, which can then be tested in future iterations.

VR has been around in our sector for a while now, with many practices harnessing it mainly as presentation tool. For us it has become so much more than this, it is a research and design tool, forming a fundamental part of our design-research approach.

It not only brings value to our clients, but also to our designers who can use it to explore and understand the potential and implications of design solutions and aesthetics even further three dimensionally.

These tools also enable us to work even more collaboratively and efficiently with the broader project team as a whole. For example the contractors and consultants are able to cost and build straight from the model, whilst tracking any changes in real time.

EBD: Can you tell us a bit more about some of your other research methods?

RH:

As part of our in depth research we also use a unique spatial analysis tool, developed by our Academic Partners at the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL, to analyse the spatial qualities of existing and new buildings. The software analyses and maps the ‘connectivity’ of different spatial configurations, and therefore the potential for people movement. As well as using the software as a diagnostic tool, we can then use it to model how various spatial interventions would impact visual and physical connectivity and integration, and the potential for greater integration across a space.

EBD: Can you give us an example of how the spatial analysis tool has potentially informed design hypotheses and even outcomes?

RH:

One example would be our work with Haymarket Media Group (HMG), where we helped them to find and create a new home for over 1,000 team members. The key objectives were multifaceted: release capital from the existing space, maximise spatial efficiency, increase collaboration, and create a sense of pride within the workplace.

The data collected through our in-depth research helped us understand their business, by identifying existing occupancy rates, densities, efficiencies, and a potential for alternative ways of working. With this deep understanding of what HMG’s people wanted from their new space, and how they were likely to use it, we were able to tailor our design strategy to their specific needs.

HMG’s old home was a 90,000sqft building, and they were hoping to reduce their footprint to circa 70,000 sqft. In the end, our analysis was able to prove that they could actually fit comfortably within just 45,000sqft.

Our research identified that on average 70% of staff were on site at any one point in time and only 46% desks were occupied. Based on this fact, and the nature of their daily activities, we recommended a more agile way of working within the new space, with 7 desks allocated for every 10 people, as well as 6 ‘alternative workpoints’ for every 10 people.

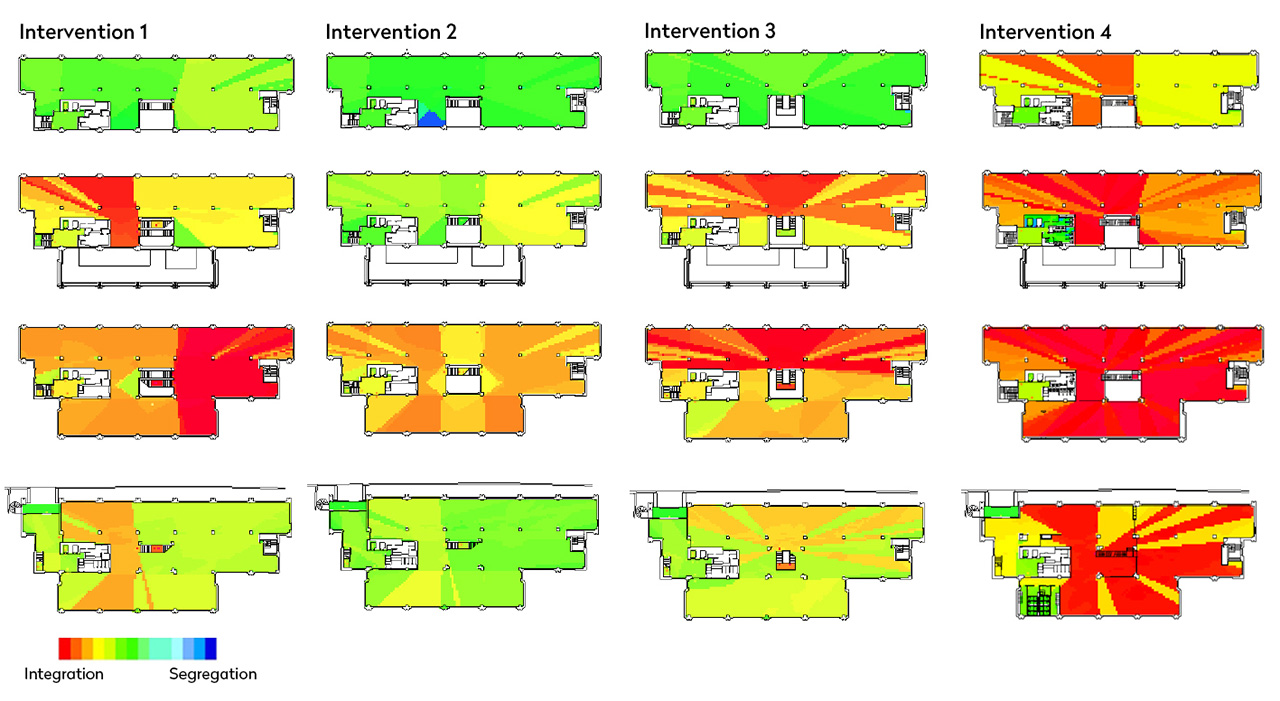

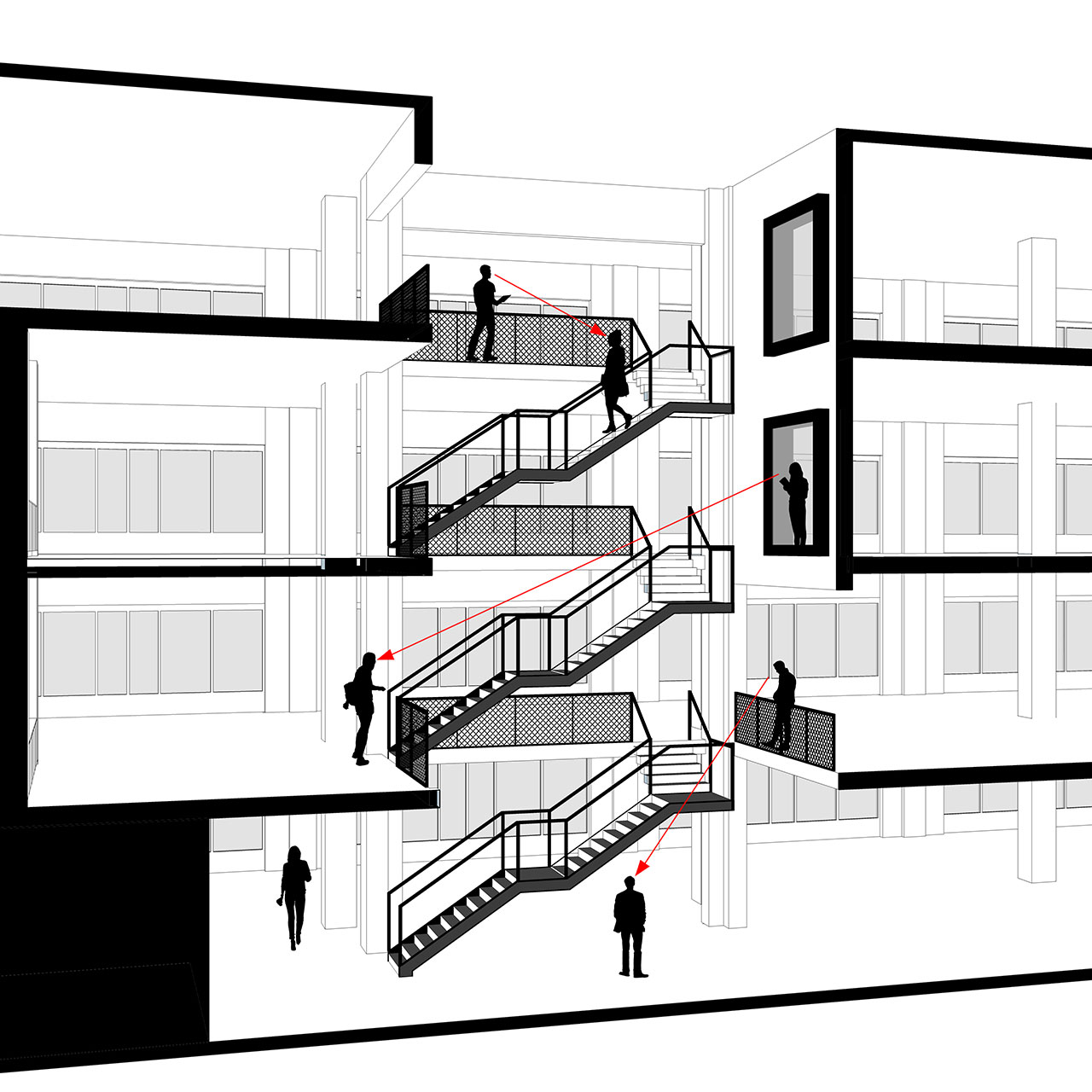

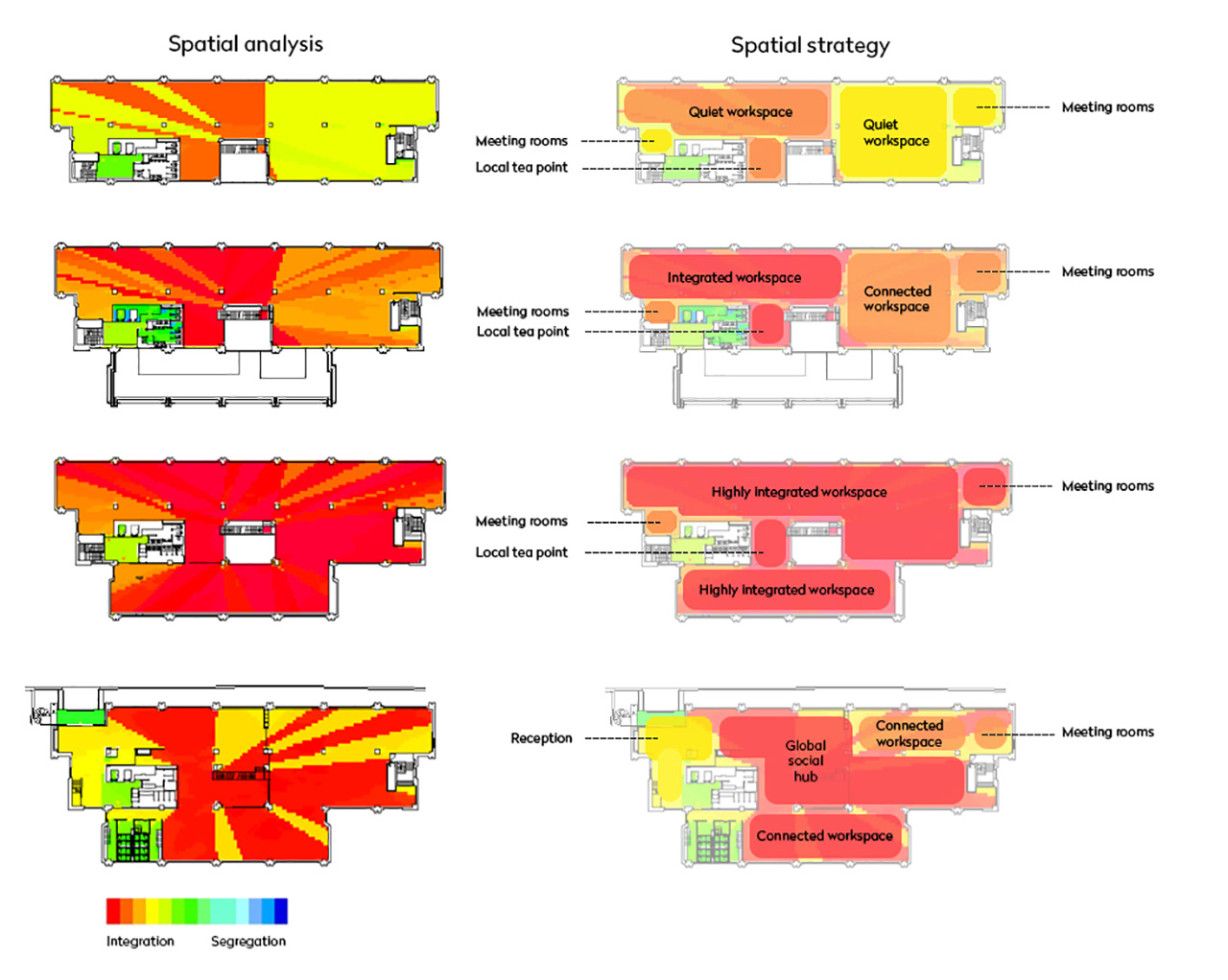

Our spatial analysis mapping tool was then used to inform our detailed design strategy for the new space. The new accommodation for HMG was split over four floors, which could have replicated the silos that formed in their previous home – and prevented the achievement of the key objective to increase collaboration between teams. The building’s disused courtyard presented an obvious opportunity to create an atrium and central staircase that could become a key spine connecting all floors. Our spatial analysis software enabled us to model the effect of different staircase positions and orientations on potential movement flows and visual connectivity between floors, and very clearly show the impact of the investment. Fig 01 shows the various interventions that were modelled, and how intervention 4 was chosen as the option that would provide the maximum connectivity through the building.

Highly connected, or ‘integrated’ spaces (shown in red and orange) correlate with higher levels of movement, and these areas are often well suited to socialising or gathering activities. ‘Segregated’ spaces (shown in cooler colours) correlate with low levels of movement and visibility, often well suited to hosting activities that require privacy or confidentiality. We developed a layout which placed key facilities in strategic ‘attractor’ positions to encourage movement around the building, increasing chance interaction and collaboration (see fig.02). We then used our organisational network analysis to position team ‘neighbourhoods’, based on their required adjacencies with other teams, and facilities.

We designed the ground floor to be divided equally between communal spaces and agile workspace for the sales team, to support the development of a more integrated and collaborative culture. This included a social hub and café that can accommodate 25% of the business seated, and can open up for the whole business to gather together.

EBD: Were you able to test the effectiveness of these hypotheses after the building was occupied? How did people take to their new environment and its new way of working?

RH:

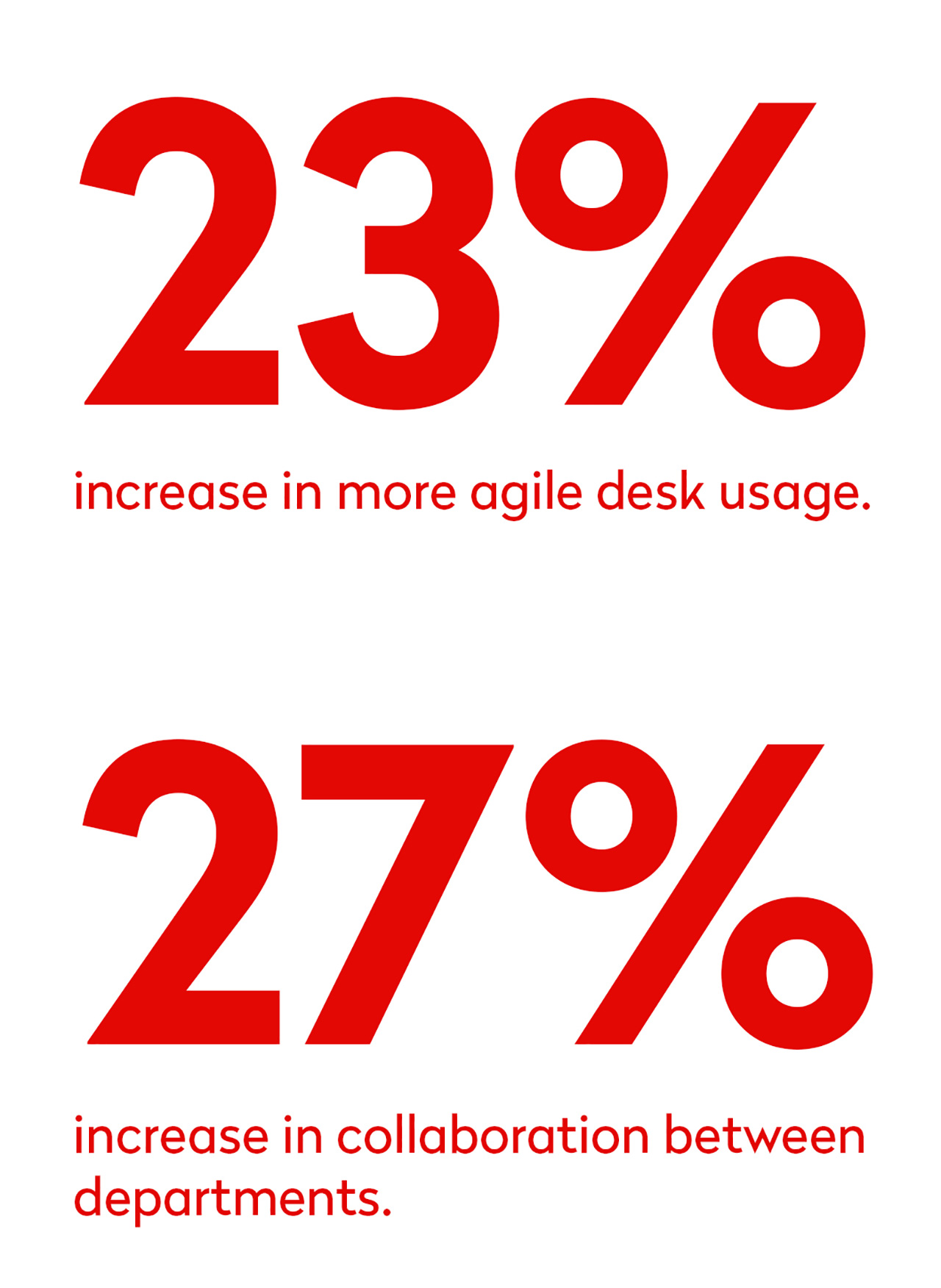

6 months after everyone moved in, our Post Occupancy Evaluation (POE) revealed significant changes to post-move behaviour patterns. There was a 23% increase in more ‘agile’ desk usage, with desks being used for shorter periods at a time, rather than being used more ‘traditionally’ all day with a break at lunchtime. Interestingly, despite the reduction in the overall number of desks, the average desk occupancy remained at just 46%, because people had embraced the new way of working and were using the variety of different types of workpoint. The number of desks lying empty all day also decreased by 16%, as people now move around and work across a wider range of positions. The results support the possibility of even higher levels of future flexibility, while comfortably accommodating more people.

Our POE also revealed that there was a 20% increase in collaboration between HMG team members within the same department, identified through surveys completed by the whole HMG team. This increase in collaboration was mainly due to shifting to a non-allocated desk strategy, allowing team members the freedom to move around and sit in new locations and next to varying members of their team. The POE also revealed a 27% increase in collaboration between colleagues of different departments, as a result of strategic positioning of attractors and the staircase to drive more movement through and across the whole building.

We designed the ground floor to be divided equally between communal spaces and agile workspace for the sales team, to support the development of a more integrated and collaborative culture. This included a social hub and café that can accommodate 25% of the business seated, and can open up for the whole business to gather together.

EBD: Are there any other examples of projects where the research techniques had a significant impact on the design thinking?

RH:

Another example is the advertising agency Iris, who felt that their existing office didn’t reflect their ethos or their values, and they came to us to help identify a new home – one that better supported their culture. Their teams were working in silos, split across three floors, so they wanted a space that would break down barriers and bring people together to create a truly integrated agency. The space also needed to create a strong first impression on visiting clients so the client journey was a key focus of the brief.

Our researchers and designers worked closely with the teams at Iris to develop a detailed brief for their property search, based on their precise needs. Our findings helped identify a new home spread across just one floor, with panoramic views across the River Thames.

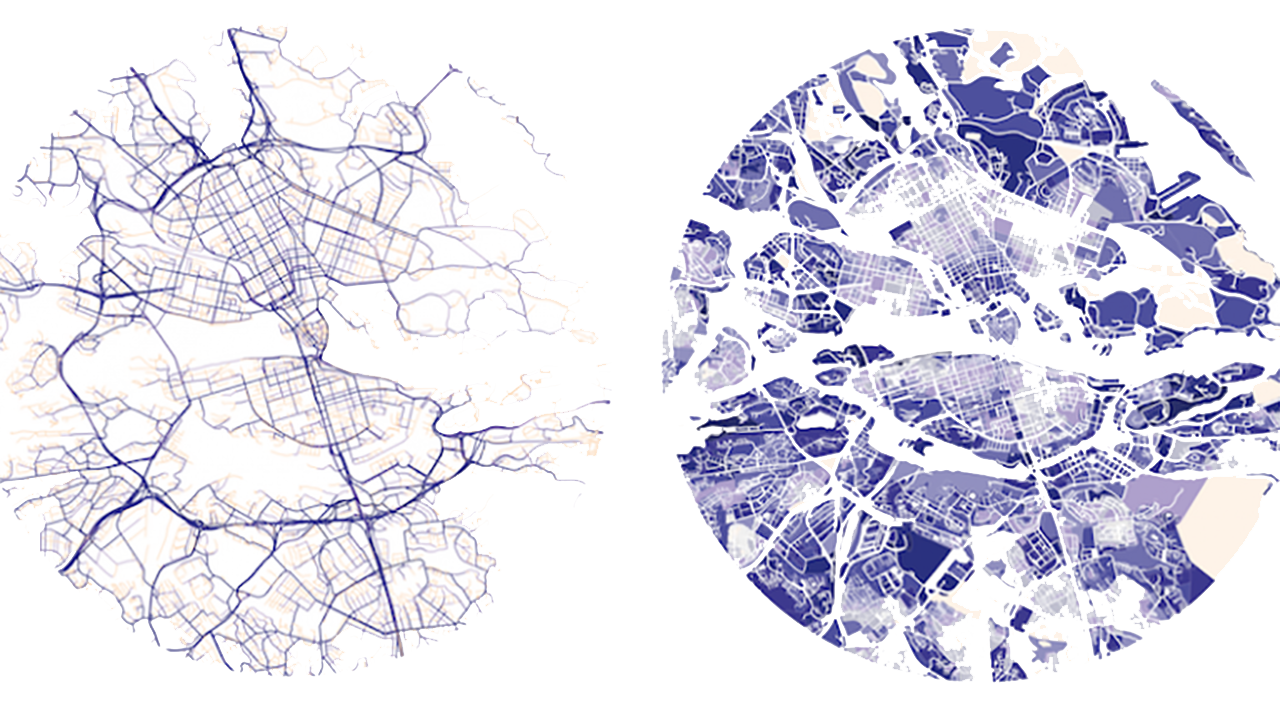

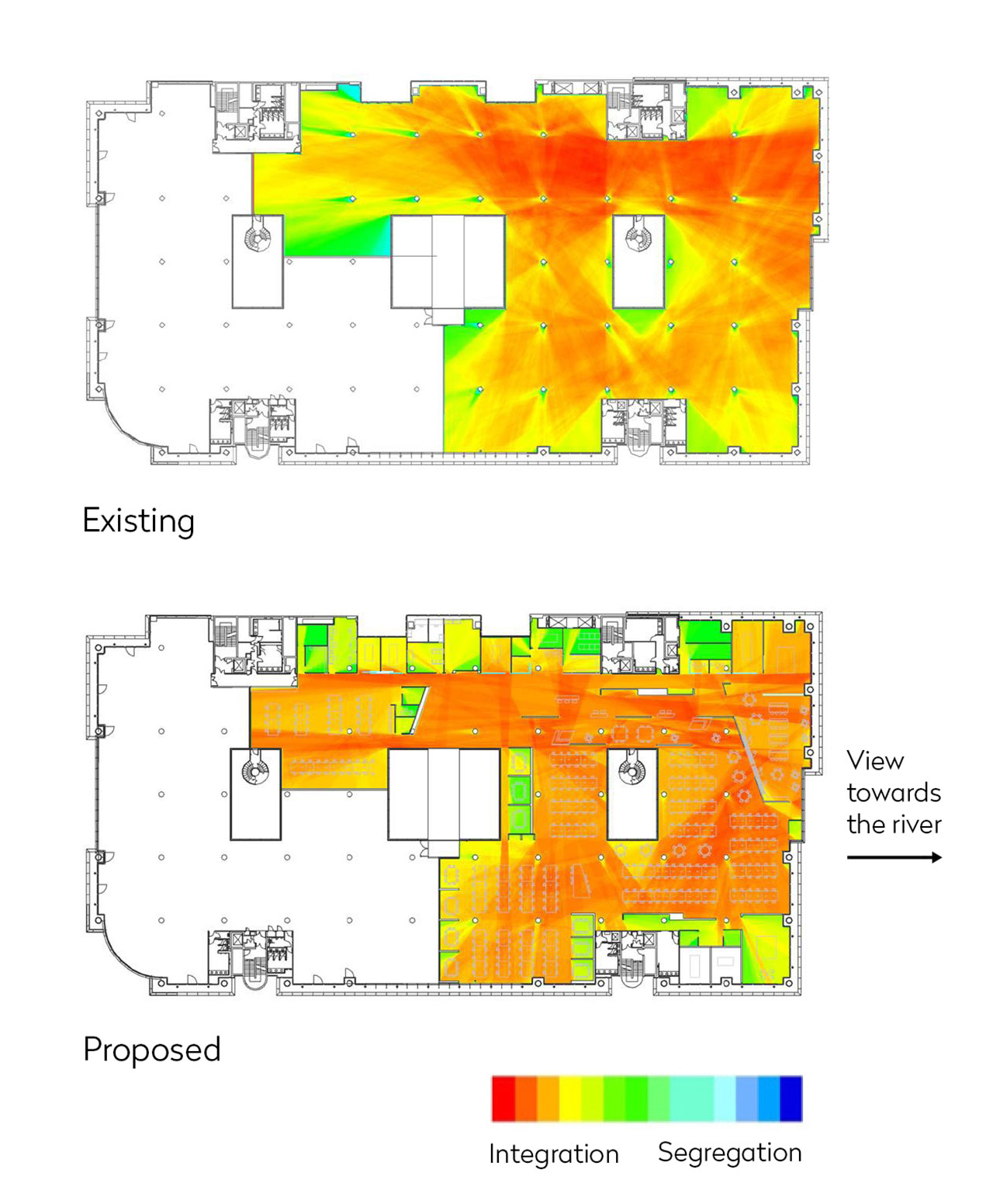

Using our spatial analysis tool, we analysed the spatial qualities of the new building, exploring the floorplate and its constituent parts in relation to how visible or accessible they were, and tested spatial layouts and interventions which would harness the natural integration of the space (see fig.03).

For example, we kept the space open to help break down the barriers between teams, and positioned partitioning towards the edges so as not to break movement and lines of sight across the floor. We also utilised the line of sight towards the River Thames at the rear of the space to form the pathway for the client journey, from reception through to the main pitch room. This pathway has good visibility across the rest of the space, giving clients glimpses into the inner workings, creativity and energy of the business.

Throughout the whole design process, we tested the space with members of the Iris team, in VR. The fully immersive and engaging nature of the experience helped them to really understand the spatial qualities of their future working environment, and consider how the space would work for them. For example, part of the brief was to develop dedicated areas for creative collaboration, so we designed a series of ‘creative hubs’ which provide a variety of flexible spaces for teams to easily discuss and present ideas. We honed the design and configuration of these with the users through our iterative cycles.

We also used the VR to introduce Iris’ external service providers to their future space, giving the opportunity for the front of house team to influence the designs of reception/waiting area and the catering team to shape the back of house spaces. Only by really engaging the future users and providing them with the tools to test the spaces were we able to ensure that they truly worked. All the feedback we received became an invaluable part of our process, helping drive and inform design decisions within the next iterative cycle.

EBD: So what’s next for Spacelab?

RH:

We’re always exploring new ways of harnessing technology to enable us to develop our approach. Currently we’re experimenting with the latest Augmented Reality (AR) tools, to enable users to experience our designs within the physical space we are proposing them for.

Our team is developing new sensors and software technology to give a more comprehensive picture of how space is used, in real time, so that organisations can make data led decisions on how to evolve their workplaces.

We’ve also started taking our research a step further by testing people’s personality types and using VR environments to explore how these relate to their functional and spatial preferences. Layering this with all our other research, and in depth engagement, enables to us to go beyond earlier reductive deployment of personality types in design and tailor spaces even more specifically to people’s needs.